Halfway through Over to You, the painter Yves Berger recounts a meeting with university students interested in his creative process. The meeting, he feels, was a “failure,” in part because of the inadequacy of his visual aid—photographs of three of his works in various stages of completion. The photographs “gave the impression of a linear process, as if Time were an arrow, whereas the real experience we have of it is made of folds, and folds within folds, sometimes touching one another.”

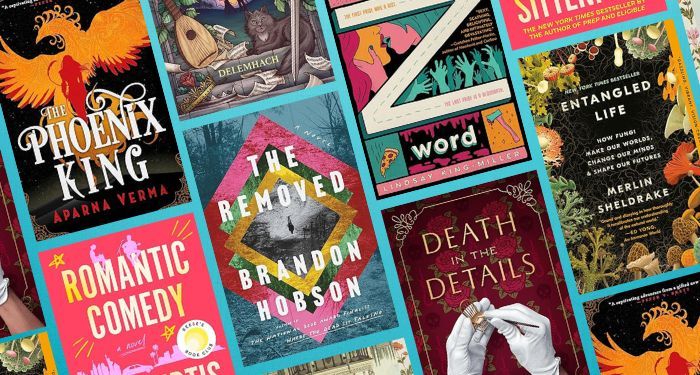

Over to You, a collection of letters exchanged by Yves and his father between 2015 and 2016, the artist and art critic John Berger (1926-2017), comes closer to giving us “the real experience” of time. In its pages, paintings from different historical periods (all helpfully reproduced in color) call out to one another: Albrecht Dürer’s Screech Owl (1508) “wink[s]” at Max Beckmann’s Columbine (1950); Vincent Van Gogh’s Still Life with Bible (1885) responds to Rogier van der Weyden’s The Annunciation (c. 1440); and John Berger’s own watercolor rose nods to Andrea della Robbia’s Madonna with Four Angels (c. 1480-1490). Throughout much of the book, the images are embedded in the letters. But toward the end, the words disappear, giving way to a visual essay—a form that would be familiar to the readers of John Berger’s celebrated 1972 book Ways of Seeing. The visual essay consists mostly of the two letter writers’ alternating drawings, which serve as a continuation of the conversation that father and son have been having with each other and with the painters of old. The book, it seems, sets out to demonstrate that “in the realm of the visible all epochs coexist and are fraternal,” to borrow from John Berger’s 2001 essay “Steps Towards a Small Theory of the Visible.”

Another important tenet of the “Small Theory” is that a painting is born out of an “encounter between painter and model—even if the model is a mountain or a shelf of empty medicine bottles” (81). In Over to You, both father and son take this idea to heart, keenly listening to what the paintings’ subjects, whether animate or inanimate, have to say. Giorgio Morandi’s “jugs and bricks,” Yves writes, are in “conversation”; Nicolas Poussin’s and Zhu Da’s landscapes, according to John, philosophize about the possibility of “eternity”; and John’s white rose, luminous against the dark, “like some figures in Caravaggio’s painting,” delivers “a message of confirmation: ‘What stands does so forever.’”

The letters, then, attempt not so much to interpret as to enliven the paintings, to make them speak with the viewer and with the world. If his father’s watercolor rose reminds Yves of Caravaggio’s works, certain details in Caravaggio’s works—such as “[t]he horse’s lifted foreleg and the man’s standing leg” in The Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1601)—are, in John’s words, “oceanic in their depth and their force.” Such language may seem to court abstraction, for if we can hitch Caravaggio’s horse to the adjective “oceanic,” then we can do the same with any number of land-bound subjects. It is also quite a leap that John makes, in his response to Yves, from “the ‘conversation’ between […] two jars” in Morandi’s studio to the conversation “[b]etween satellites and the earth.” Or how, for that matter, do we picture what Yves calls the “gap between […] the visible and the invisible”?

Yet the impossibility of picturing may be precisely the point: to an unusual degree for a book on visual art, Over to You dwells on the formless and the unseen, on painting as “the recuperation of the invisible.” The phrase first occurs during John’s discussion of Moss Roses in a Vase (1882). In his interpretation, Édouard Manet’s still life is not still at all: “Within the glass, the natural forms […] are decomposed. They become nonfigurative. We are looking through the glass at antecedent raw material.” This reads like a statement on the artwork’s prehistory—on what it had been before it became an artwork. But John goes still further: what fascinates him, and his son, is “whatever it is that precedes and follows existence.”

This fascination is obvious in how often water—widely thought to have brought forth the first forms of life—seeps into the conversation. Water is not only in Manet’s vase or (metaphorically) in Caravaggio’s painting. It also glistens from a window of the train where Yves is writing one of the letters; it runs under the bridge of his childhood recollection; it engulfs a meditation on the act of painting, when Yves compares the lure of artmaking to the lure of the sea depths (as evoked in Luc Besson’s film Le Grand Bleu).

Like continents, the paintings in the book are connected by these oceanic undercurrents, appearing as fruits less of individual creative geniuses than of nature itself. (Indeed, the way the book uses water to link the paintings and the natural world reminds me of how Jeff Wall links nature and photography in his essay “Photography and Liquid Intelligence,” as well as of Kaja Silverman’s perceptive reading of this essay in The Miracle of Analogy.) For some images in the book, this is almost literally true: in the visual essay, among father and son’s drawings, we encounter a print from a honeycomb and a photograph of an outline traced by Yves on a snow-covered bench—a rabbit with a wood knot for an eye.

But nature also collaborates with the two artists in subtler ways, and the descriptions of this collaboration are among the most memorable passages in the book. John recalls how, as an art student, he mixed paint using cobalt powder, whose dazzling blue “[was] there before any eye had evolved.” While preparing titanium white, Yves achieves “[a] fresh honey-like texture,” then lets his eyes wander to the beehives visible through an open window. Painting—and writing about painting—become a celebration of the vitally concrete.