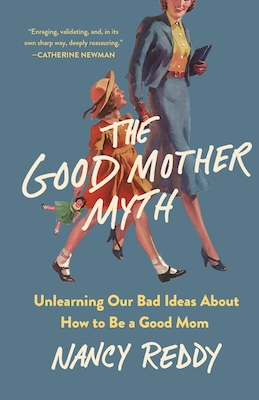

Though I shill out parenting advice for a living, books about it often make me want to scream. That’s because most of them take for granted that a small set of research by middle-class white men (and later, women), conducted mostly on other middle-class white people, is infallible. As someone who’s witnessed the complexities of research with children firsthand, I’ve always been wary of this body of work. Now, with Nancy Reddy’s new The Good Mother Myth: Unlearning Our Bad Ideas About How to Be a Good Mom, I have proof.

The book, part-memoir, part-analysis, follows Reddy as she takes on some of our most seemingly infallible ideas about parenting, herself in the throes of early motherhood. We learn about John Bowlby, who concluded that post-World War II orphans were traumatized not by war, but by the absence of their mothers; Harry Harlow, who noticed that Macaw monkeys preferred a wire and cotton “mother” to a sharp, abusive one, even when she had milk; and Mary Ainsworth, whose “Strange Situation” claimed to predict psychological well-being by a two-minute experiment with weird people, in a weird room.

These characters, and others, are exquisitely exposed by Reddy, who conducts an autopsy on not just the shoddy research of this period, but the social and cultural climate in which it was conducted, and the personal shortcomings (In Bowlby’s case, some might say vendettas) of the handful of mid-century researchers who still deeply influence parenting advice today.

I sat down with Reddy over Zoom to talk about hauntings, collective caregiving, and the process of writing her first non-fiction book.

Sarah Wheeler: You talk about how there’s no way to make motherhood easy, but there are lots of ways to make it harder. Can you talk about some of the ways that motherhood is made harder for us?

Nancy Reddy: I think it’s everything from the big national lack of a safety net, like access to good prenatal care, maternity leave, affordable childcare, all of those kinds of huge structural things that make parenting in America uniquely brutal.

And then there’s also all the cultural stuff around what it means to be a mom. At the center of the book is the idea that being a good mom, heavy scare quotes, means that you’re this omnipotent being who can just do it all yourself, powered by, I don’t know what, love and a superhuman need to never sleep. Parenting, like so many things in America, ends up becoming this really individualized and very isolating experience and I think a lot of moms feel pressure to do it correctly, themselves.

Early on, there was a mothering group, at the natural parenting store where I went for prenatal yoga, called “Cuddle Bugs.” And I remember thinking, “once I’ve gotten this figured out, then I’ll be ready to be among all these other moms,” instead of being like, “take your messy self and go, talk about what is happening and what you need.”

SW: One of the things that is so essential in your book is the idea that all of this pressure doesn’t come from nowhere. You trace it back to these iconic researchers of the mid 20th century, whose work still greatly impacts motherhood. You have a lot of great scenes of your new motherhood being almost shadowed by the work of these old white men.

NR: When I started the research part of the book, I was really trying to figure out where did these bad ideas come from? What is the the origin of this mythology? What I discovered is that so much of what got circulated, and still gets circulated as science, really came out of a very particular cultural and historical moment. This is post World War II. There were a lot of women and mothers who had been working in the war effort who sent their babies to state supported daycare, where they did really well and the mothers loved it. And then all of a sudden, there’s men returning home from war, and there’s a lot of people in political life and public life worried about what’s going to happen. So it’s not an accident that the science that’s being done at that time supports those economic imperatives and gender ideologies. That they find that the most important thing that your baby needs is a mother to be home and constantly available all the time, therefore you can’t possibly work. It just happens to suit this economic agenda of getting men back in the workforce and women back at home.

SW: Can you trace some of the early research, let’s say on attachment, from that post World War II moment where it’s being conducted to you sitting in the nursery with your first born?

NR: Absolutely. I think the language and the images that we have are really powerful conveyors of that. Before I had my first son, I had this image of myself sitting at a desk typing my dissertation, with the baby in one of those [wraps]. And it was this image of this incredibly present mother. That’s an image that goes back, certainly to Harry Harlow’s monkey research, the newborn macaque monkeys clinging to the cloth mothers. That became this really iconic image of what it means to be a mother, to be totally available and totally selfless all the time.

SW: And those images stuck, right? An Instagram influencer making some one line comment about attachment or being present for your baby, that’s kind of a paraphrase of the paraphrase of the paraphrase of Harlow? You explain so well how the foundation for all of those paraphrases is actually quite shoddy, and not just politically problematic, but scientifically.

NR: Harlow is a really fascinating example of what happens when scientific research escapes academia: how it circulates and recirculates, and how much nuance is lost and how things get used for other purposes. In 1959 he gave this talk as president of the American Psychological Association (APA) called “The Nature of Love.” He played 15 minutes of a video where you see the baby and the cloth mother. And he says something like, ”Look at her. She’s soft, warm, tender, patient and available 24 hours a day.” And that’s really what got picked up about what it means to be a mother. But even in that talk, there are these little moments that are actually pretty radical, where he says, for example, if the important variable is not lactation but comfort, men could be good monkey mothers too. And nobody picks that up! Like, Women’s Wear Daily is not talking about it.

SW: We’ve also talked about the level of subjective interpretation of some of these findings. It’s a pretty big leap to go from monkeys with a wire mother covered in cloth to actual human interaction, right, which is so much more complex? So even just that suspension of disbelief is intense.

NR: Also just methodologically, it’s wild that he created this mother surrogate to try to understand what would happen with monkey babies, and then was very willing to go along with it when the popular press extrapolated from monkeys to human babies.

SW: And you make the argument that the way that academia works encourages us to make these pretty simple and kind of absolutist conclusions, in addition to the cultural and economic incentives to create research with these results.

NR: For me, there’s an important disciplinary distinction. A lot of attachment theory is grounded in either lab science, like Harlow’s work with the monkeys, or these laboratory procedures that came out of psychology, like the Strange Situation. You bring your baby in, they do a little experimental protocol, the whole thing takes 20 minutes. They tell you what your baby’s attachment style is, and that’s the end of the story. It’s very great for researchers, because you can do it really quickly. You can reproduce it. You can publish fast. You can train grad students to do it. But I’m not convinced that it actually really tells us anything very interesting about human relationships.

SW: I love the parts of the book where you talk about Margaret Mead and the contrast between Harlow and Bowlby or Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation, which was very artificial, and research on parenting that actually looked at real mothers.

NR: Yes, the counterpart to that, I would say, is the work that anthropologists do–deep ethnographic work. Margaret Mead is one example of that – going to a place, living in a community, learning a language and trying to do participant-observation. Mead, of course, is complicated. She did write about so-called “primitives” in Samoa. She’s still a white lady, going abroad and taking all of that with her. But what was really interesting to me was that she went to Samoa as a very young woman, spent time there, really got to know the culture and then brought back with her these ideas about parenting that she put into place when she had her own daughter. She observed that community, and she saw that it was not women in single-family houses raising children by themselves while their husbands were off at work. I think that that time really showed her how crazy the American ideals of the time were. And so she always lived with other families. She called it a “composite household.” She really intentionally surrounded her daughter with other adults and with other kids. And I think that’s pretty amazing, but you have to be very intentional in seeking that out in our culture.

SW: Speaking of American parenting, I thought you wrote so well about how our good mother myths uphold the work of capitalism. You have this lovely quote that’s basically, if we aren’t stuck in our homes, being anxious about our kids, then we’d be out on the streets, revolutionizing. Can you elaborate on that?

NR: It’s this optimization that you’ve written about too. Emily Oster is not to blame for it, but I think she’s a symptom and driver of that culture. Our culture pushes us to optimize these things for our kids in a way that is expensive and incredibly time consuming and probably not better for them. If more parents took the energy and the social capital that they were putting into competitive sports and fancy instrument lessons, and focused that on rec sports and music in the schools, and lunch programs, we could use those resources to benefit lots of kids, and not just our own.

Dani McClain’s book We Live For The We talks about the way that for a lot of Black mothers, motherhood becomes a springboard into forms of public service. I think it’s the opposite of what we’re talking about, where it’s not how can I get this for my kid?, but how can I get this for lots of kids? I also think about an organization that I’ve gotten involved with in my town that’s opposed to the proposed closure of our only majority-minority school. Through my work with that group, I’ve gotten to know one mother in particular who has these incredible research skills, where she’s been able to figure out all of this stuff like, how can we make sure the kids in the town adjacent to ours can be part of our little league? How can we try to get solar panels on the roofs of our buildings? Because that would save money, and enable hire more teachers, right? And I just that’s been such an inspiring example to me to be like, look at Karina using these skills that to do things for kids who are not her kids, you know?

SW: Through the book, you are kind of offering this, you know, it’s almost like a public service announcement, you know, that is your own story, which you’re very generous about. But also like, “Hey everyone, most of this kind of noise that you’re getting as a parent comes from a few influential researchers, in the last century. And guess what? I got news for you, it’s not great research!” So, thinking about what to replace those conversations with feels really valuable.

NR: I had a friend early on who was like, “But who do those ideas serve? Who is benefiting?” For me, the thing that I try to really listen to is just that should, like I so often feel like, well, I should be doing X, Y, Z, and that’s that should is almost always a sign that the thing I feel like I should be doing is actually not what my family needs, but is responding to some sort of external pressure, right? And oftentimes, when we put it down, it just feels really good to be like, “Nope, we’re actually not going to do that. Like, that’s not what we value.”

SW: You open the book with this stunning line “before I had a baby, I was good at things.” And it makes me think about how the forces you’re describing link up with the way that particularly white, middle class women are raised to be kind of problem solvers which added to this feeling of incompetence for you. And do you see that incompetence as further driving cycle of individualism?

NR: Not just that, but I think also the professionalization, right? It is so easy to see motherhood as a professional identity– that it’s the most important job in the world, and it’s so high stakes, it can only really be done well by the biological Mother and and and you should bring all of the skills from your education and your professional life to bear on this work. And I am really aware of how that approach to parenting sucks the joy out of so much of it. If you’re trying to improve your performance as a parent, it’s really hard to actually connect with your kid, which is where the joy is.

SW: You’ve talked about how these motherhood myths obviously harm mothers, and also harm children by distracting their mothers from the real pursuit of motherhood, which to me is achieving equanimity and acceptance while being present in a reasonable way, and modeling how to be a human. I think maybe you would agree with that? But how do they also harm other folks? You talked about how fathers or allo-parents are left out of this early research.

NR: Mothers are the most obvious target, but I also think it’s really bad for men. Women, whether you become a mother or not, have this whole motherhood advice industrial complex aimed at us. I do not wish that same kind of fire hose of expectations to be aimed at anyone else. But I think men oftentimes don’t have much guidance at all. I think about the men in my life who are mostly just trying to do a little bit better than their dads, or sometimes a lot better than their dads, but they don’t have a lot of modeling. I at least have the option of a Cuddle Bugs. I’m not sure if there was a father’s equivalent to that. For men, there’s so often not much in the way of expectations or support or community. And I think it’s harmful, if you assume that motherhood is natural and the inevitable destiny of every woman, that’s pretty bad for people who don’t want to have kids, right? Some of the people who have been the most meaningful supports in our family have been people who don’t have kids, but who really love my kids. If we have a culture that looks on women, especially those who don’t have kids, with suspicion, it harms those women, and it harms families.

SW: I’m also wondering how the myths dispelled by the research that you focus on in the book include or exclude women of color, mothers of color, working, working class, and poor mothers?

NR: The mythology of the good mother has always been—from the postwar period on—married, straight, middle class, upper middle class and white and by definition, excludes anyone who doesn’t fit those boundaries. It excludes women whose children are disabled, who are themselves disabled, women of color, and anyone who’s not a gestational parent.

SW: You’re no stranger to the world of motherhood and creativity – the anthology you co-edited, The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood, is beloved by many, and in your Substack Newsletter, Write More, Be Less Careful, you have a series where you interview writer-caregivers about their craft (we met in 2023 when you interviewed me). I’m wondering how those conversations informed your experience writing this book, as someone who still spends serious time caring for children?

NR: One thing that comes up a lot is feeling totally crunched for time, but also a changing relationship to time. There’s kind of the businessman’s approach to time, where it’s like nine to five and you’re putting in your shift at the writing factory. And I think that caregiving really forces us to think about time differently, and there are some moments in both writing and parenting where time feels stretchier and more expansive. Like if you’re a new parent and you have 15 minutes where you can write, you actually can do a lot in those 15 minutes.

One other thing that’s been coming up a lot recently is the idea of being gentle with yourself and being gentle with others, which I appreciate so much as a perspective, maybe because it’s not one that’s been easy for me to adopt. Beating ourselves up never actually gets the writing done or makes it better. One of the big things that that series has really shown me is how inspiring it is that there are so many of us who are just trying so hard, and we are out there and it’s valuable and it’s important, and that the process itself is valuable.