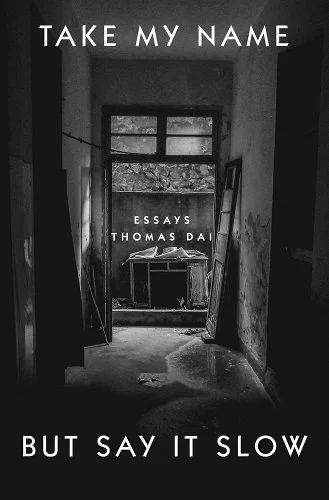

“Southings,” An Excerpt from Take My Name But Say It Slow by Thomas Dai

Southing, noun

1: difference in latitude to the south from the last preceding point of reckoning

2: southerly progress

The cicadas began to arrive in the South in May. I suppose “arrive” is the wrong word, as the insects had been in the yard for two years already when my parents bought the property back in 2006, their bodies buried eight or more feet deep in the soil, insect clocks set to a seventeen-year timer. They’d grown older in our unwitting company, outlasting two chickens, four goldfish, three graduating seniors, and at least a couple hundred rabbits. Like billions of their brethren across the country, the cicadas were now emerging in their blackened, red-eyed old age, tymbal subwoofers pumping out this endless, dirge-like song.

“These bugs are seventeen years old,” I tell my mother. “The same age as Airik.”

“Oh really?” she says, actually impressed. “He’s been eating them. I hope they taste good.”

Mom is showing me around the backyard as Airik the shepherd-chow mix shuffles along in our wake, a belly full of his contemporaries. Almost two years have passed since last I came south. While I was away, my younger sister graduated and moved north for college, leaving my parents with an empty nest. Dad has gotten into home surveillance. He’s acquired a fleet of drones which he uses to take aerial snapshots of the neighborhood. (One went AWOL in a neighbor’s tree, and Dad’s been too embarrassed to walk over and ask for it back.) Then there’s the cheap cameras he’s placed around the house, their live footage streamable on his phone. Each night since the pandemic began, Dad’s sent the family group text a screen grab from one of his feeds—usually a pixelated image of Airik asleep on the porch—accompanied by the same, repeating message of “Good night and good luck!”

Mom, for her part, has pivoted from childrearing to plant husbandry. She shows me the vegetable beds out back, each haphazardly planted with Chinese watercress, Chinese chives, Chinese eggplants, tomatoes, strawberries, coriander, a lone bitter melon, some swollen peppers and shriveled string beans. There are white irises in bloom all around us, and a big metal pail filled with dark water and what I think must be lilies.

During the years my siblings and I were growing up here, my parents never seemed to take a shine to the South. They never went on hikes in the Smoky mountains like they do now, or kayaked in the flooded quarry just south of downtown, or had the time to get involved with neighborhood beautification. And yet, I don’t remember them ever complaining about feeling isolated either. “It was very simple,” Dad tells me. He had a three-point plan when he came here: study hard, get a job, raise a family in America—a plan he has executed up to this point. When I ask him if he ever felt unwelcome in Tennessee, he responds adamantly in the negative. Back then Japan was America’s main economic rival, and in his account, Americans thought of China, not Japan, as their main ally in the East. “I always think immigration is the key thing,” he says; letting migrants in should be “compulsory,” as long as the immigrants are as diligent as him.

My father became a citizen the moment he was eligible, and when money was no longer a problem, he and my mother acquired green cards for their parents so they could visit us whenever they wished. The long-term goal was always to bring the whole family over, to have my grandparents and uncles and cousins all settle in Tennessee. That never worked out—not least of which because China is no longer a place that highly-educated Chinese people feel they need to leave. Growing up, I always thought that maybe my parents were lonely here in the South, and that maybe if they’d made more of an effort to assimilate, not just in terms of citizenship, but culture, they wouldn’t have missed their family so much that they needed their family to come over here.

What friends my parents had when I was young were all drawn from the small and frequently drained pool of local Chinese immigrants—friends who were always decamping for other states or reverse migrating back to China. My parents sometimes speak of following suit after they retire, of pulling up stakes like the cicadas are doing now, circling back to the dappled treetops where their own, cyclical lives began. A Chinese treatise on war, the one not written by Sun Tzu, describes a maneuver known as “Slough off the Cicada’s Golden Shell,” in which a retreating force leaves a copy of itself behind on the battlefield to confuse a gullible opponent. Right now, my parents’ backyard is covered in these decoys. They crunch like packing peanuts beneath my feet.

If my parents ever did go back to China, I’d feel like one of the decoys: an amber-colored molt left behind by my predecessors. These shells seem more intact than former selves have any right to be, each with a telltale tear by the head through which their wearers got away. Seeing my parents’ yard covered in cicada shells was reason enough to come home this summer: how a skin deprived of its body still stands, clinging crab-like to fence posts and stems. One brisk rain might wash them away, but up until now, they’ve stayed.

My mind is often drifting southwards even as my body stays sequestered in the North.

I was born and raised in the American South, in a suburb of Knoxville called Farragut. For ten of the past fourteen years, I’ve lived in New England, with the remaining four split between China and Arizona. Yet none of these places have felt like a permanent backdrop to my life in the way that East Tennessee once did. I know this because my mind is often drifting southwards even as my body stays sequestered in the North. I’ll be riding the subway, looking absentmindedly down the length of the train car, and suddenly the entire locomotive spyglass will be filled with this verdigris flush, a green that rushes along beneath the city on unseen tracks, reminding me, invariably, of the South. In other words, the trigger is environmental: the way the air is balanced today, the glossy depth of a field my partner and I pass while driving from one Boston suburb to the next, looking for passable dim sum. This field will look, in the brief glimpse of it I can catch, fresh, perfect, unmown.

And so we come to the crux of the matter: a Southern field I once knew. I hesitate to even describe this field, as it really was a prosaic space, a pastoral interlude in the middle of suburbia, as neutral and inviting as only a field can be. Obviously there was grass in this field; that, and a few trees. I cannot call up specific names for those trees, nor for the many birds, reptiles, and insects that, in addition to me and the cows, must have inhabited that space. Knowing the field in that way never interested me. The field was this outside space, one I did not wish to assimilate into my world, even as I spent hours exploring its expanse. Nowadays, I consider that field—or rather, my attachment to it—as possibly the most Southern thing about me. Although I lack most of the outward tells of Southernness, which is to say I speak unaccented English and have a face that is neither white nor black but yellow, that field places me in the South. My memories of it are full-body ones: overgrown, terrestrial, musical as any sentence by my hometown’s literary hero James Agee, lit up like a landscape shot by Sally Mann.

I used to practice wushu out in the field, far away from all my neighbors’ prying eyes, stretching and high kicking and making patterns with my limbs. For years, I’ve had this recurring dream where I’m back there, dressed in my East Tennessee Wushu Team uniform of sky blue polyester, alone and running. It’s dawn or early evening, the field’s grassy swells covered in fog, and as I run, I start leaping at the crest of each earthen wavelet, and these leaps keep stretching out until I am gliding through air like the warriors in Wuxia films do, a body no longer in touch with the ground, predisposed toward flight.

While I’m no expert at dream analysis, the subconscious speaks pretty loudly in this one. I loved that field, but that field belonged to someone else, a farmer who owned the cattle and harvested the hay. Technically speaking, I was a trespasser on this man’s property, and so my relationship to his field might as well be my relationship to the South as a whole: an enduring fidelity I feel for a space I could never, fully own.

I’ve been thinking more than usual about this: the place which Asians do or don’t have in that part of America which gets defined as the South. Most of the scholars I’ve consulted on the topic tell me that “Asian America” and “the South” rarely, if ever, converge, making the Asians at the center of this Venn Diagram seem like poor navigators, honorary Californians who somehow wound up in Tennessee. There are many reasons for this incongruence (what the editors of an anthology called Asian Americans in Dixie refer to as the Asian Southerner’s “discrepant” status). One is simple demographics. Even though Southern cities like Atlanta and Houston boast large and rapidly growing Asian communities, proportionally fewer Asians live in the South than in the West or Northeast. Another factor might be spin. Asian Americans are consistently seen and represented, even by ourselves, as “new” Americans, and the spaces and timelines we populate are reliably contemporary or futuristic. We are proprietary products, that is, of the long 20th century as well as harbingers of the 21st. Our Oort cloud of associations includes “fusion cuisine,” “forgotten wars,” “globalization,” “foreign imports,” “software engineer,” and “R&D.” On the other hand, the South and its people are famously anti-progressive, old and loamy and deeply rooted in all things. Despite all the hubbub about so-called “New Souths,” Southern identity is perceived by most to be marooned in the before times, somewhere betwixt Civil War and Civil Rights. Asians were here in the South back then as well (see the “Manilla men” of the Louisiana bayous, the handful of indentured coolies who labored on Southern plantations, the eight thousand plus Japanese incarcerated in Arkansas during WWII), and yet our historical presence in these parts has been easy to forget, our present-day contributions limited to a smattering of Indian-owned motels and Chinese-owned grocers.

Asians can rarely tell where they fit within the South’s racial pecking order.

As the critic Leslie Bow writes, Asians in the South have long occupied a kind of “social limbo, a segregation from segregation,” by which she means that Asians can rarely tell where they fit within the South’s racial pecking order. One could of course make the same argument about Asians elsewhere in this country. Outside of a few urban enclaves, aren’t most Asian communities so small as to barely register within any local patchwork of social relations? Perhaps the aberrancy of Asians in the South is simply a difference in degree, then—we feel more like a minority here than elsewhere, and so more existentially adrift. But the difference also has to do with how the South has itself been framed as a space apart, home to the obese, the poor, and the excessively religious; the bigots and the rednecks; the winsome folk singers and daredevil Davy Crocketts. This vast and heterogeneous region has so often been held up and put down as a different, phantasmal America, and so being Asian in this space means embodying an exception within the exception—an anomaly, squared.

One core tenet of Southern distinctiveness is the intense, almost maudlin connection good Southerners are supposed to feel for the land they were raised on. As a college student in the North, I once attended the office hours of a teaching assistant who’d also grown up in the Tennessee Valley. White Southerners I knew at my school often spoke of feeling out of place there, outclassed by an even older WASP elite. (Some of these Southerners even banded together to form a short-lived “Southern Culture Club,” spearheaded by a girl I knew from my freshman dorm who claimed direct descent from Robert E. Lee.) My teacher probably had little interest in discussing Southern identity politics with me, but she also didn’t balk when I asked her about her upbringing in East Tennessee. She told me she’d grown up on a farm north of Fountain City with chickens and goats and brothers who shot squirrels, and said that it was only after she, too, left the South for college that she realized hers was not a “normal” American upbringing. Most of the people my teacher knew growing up were only one or two generations removed from agrarian life. This closeness to the land, or at least the land’s memory, was what distinguished Southerners from everyone else.

Perhaps this is also why the confluence of Southernness and Asianness has continued to elude me. The former is premised on land: stolen land, broken land, land which has been worked over for generations, but land nonetheless. The latter—if it’s built on anything at all—is built on dislocation and diaspora, on the dispersed and fragile networks forged by those who’ve learned to dwell in spaces few and far between.

This is all to say that there are Asian people in the South, millions of them, in fact, but that doesn’t mean they feel Southern.

On the screen porch in Farragut, I sit with the dog and the sweltering air. I rock back and forth in the chair as sunlight sews clever little embroideries into a white wooden table. This is the table where I learned how to write—you can still see the imprint of old words, both Chinese and English, grooved onto its surface—and also the table where I once laid a dead king snake after a long walk through the field, its sleek length banded black and white, one of those perfect found objects of summer.

Airik’s old, but he’s only recently begun to show it. He’s acquired a few things since last I saw him: rheumy eyes, occasional fits of flatulence, a custom-built staircase with a railing leading down into the yard (no one with hands ever uses these stairs, but my parents’ home insurers insisted on the railing for liability reasons). Petting him as he pants, I pick three or four ticks out of his fur, each like a botoxed raisin.

Here we are: a man and his dog on the porch, listening to cicadas. Is there any configuration more Southern than that?

Since none of my friends live in town anymore, I spend most of my time at home just driving around, indulging my private nostalgia while playing the part of the Asian tourist. I go to places I never paid much attention to when I lived here, places called “Founder’s Park” and the “Farragut Folklife Museum” inside of town hall, where one can admire an oil portrait of David Farragut—first admiral of the U.S. Navy, born not far from this spot!—and scope out his wife’s collection of fine china. I even go into Knoxville itself, my hometown’s recently resurgent core: Gay Street and Market Square, a weather kiosk installed in 1912 that no longer tells the weather. I visit one boring municipal museum, and then another, loiter about a park commemorating James Agee just down the street from my parents’ first American apartment. There is a sign by the river welcoming pandemic travelers. “For the Love of Knoxville. Travel Safe. Stay Safe.”

I guess this is “the South,” or my slice of it at least. My South is that austral shiver I get when I hear Dolly Parton’s “The Bridge.” It’s the mountains blued out by distance which are permanently fixed into a folksy still-life in the back of my mind. It’s the field: the field as it was, and as it is. When I’m back in this South, I’m always trying to parse where myth and land part ways. At the Museum of Appalachia, I walk around a barn dubbed the “Appalachian Hall of Fame,” squinting at all the writing on the wall: “These are our people. World renowned, unknown, famous, infamous, interesting, diverse, different. But above all, they are a warm, colorful, and jolly lot. In love with our land, our mountains, our culture.” The barn is stuffed with quilts and old photographs, mandolins with frayed strings, the kind of apocrypha (e.g., a child’s sled owned by the founder of Dunkin Donuts, who years ago vacationed in East Tennessee) that only such institutions care to retain. Here there is a corner devoted to “Misc & Unusual Indian Artifacts,” and beyond that, a bunch of placarded exhibits bearing the colorful stories of Appalachian Hall of Famers, stories like that of Asa Jackson’s “Fabulous Perpetual Motion Machine” and “Old ‘Saupaw’ the Cave Dwelling Hermit and his Little Hanging Cabinet.”

None of these stories speak of Appalachian Asians, or of Asians in the broader South. There is no such “representation” to be had at this museum, unless you count, as I do, the kudzu vines conquering all the nearby trees or the Indian peafowl roaming the grounds, pecking away at some invisible prey.

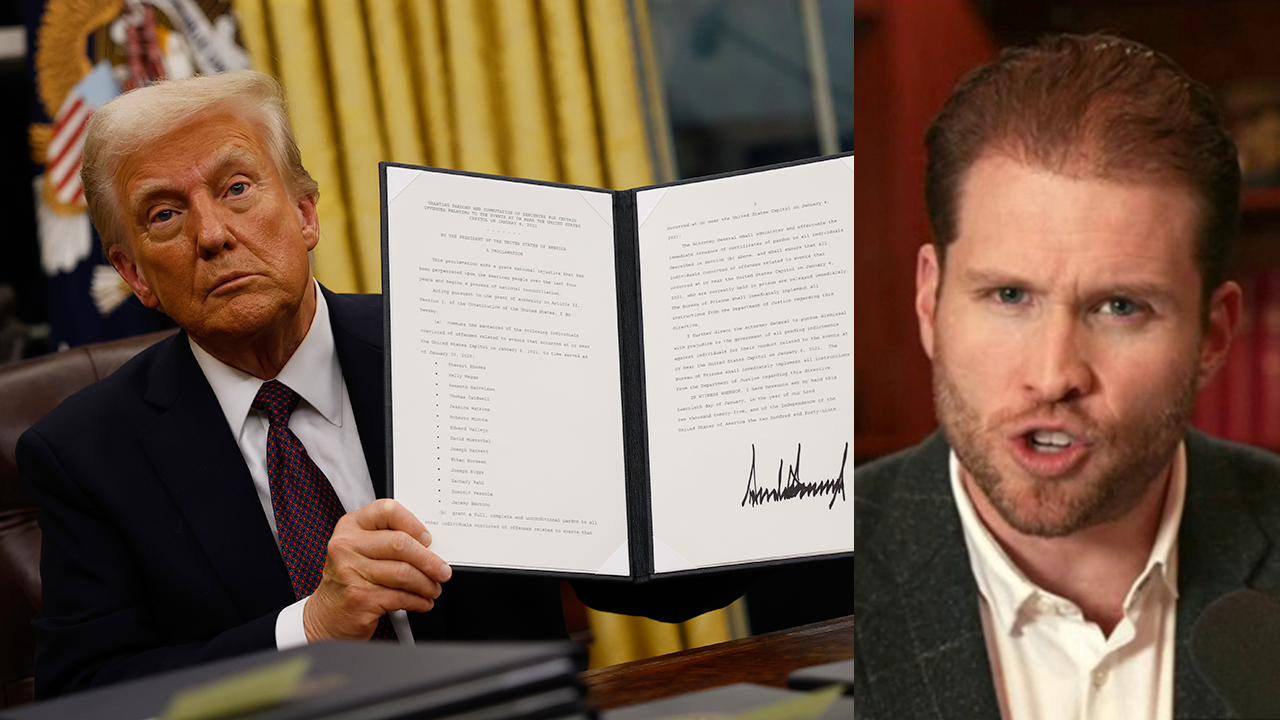

Several decades ago, another Asian named Choong Soon Kim came to the South in order to study it. Much like my own parents, Kim arrived here as a doctoral student. He wanted to write a treatise on Southern culture, a deep dive into “the ‘innards’ of the South” as told through the refracting lens of race. The resulting book—An Asian Anthropologist in the South: Field Experiences with Blacks, Indians, and Whites—is not so much an objective account of Southern race relations as it is a reflection of how one Asian anthropologist was received in the South.

That reception was not always a warm one. Children followed Kim down the streets of Georgia, chanting “Chinaman, Chinaman.” Multiple informants, mostly educated whites, refused to shake Kim’s hand or answer any of his questions, even as they spoke deferentially to his white colleagues. Someone broke into Kim’s motel room to steal his field notes and left a threatening note on his car. At one point, a cop bluntly told Kim that no foreigner from an “underdeveloped” country should have the gall to question Americans about their ways. And yet Kim refuses to interpret any of these events as racially motivated, writing in his book’s epilogue: “I wish to emphasize that I have never been subjected to [racial discrimination] during my ten years of living in the South.”

Confident as Kim may have been that he had never experienced Southern racism firsthand, he nonetheless concludes that Asianness and Southernness are immiscible entities. Unlike the white anthropologist who tries to “go native,” Kim realized in the field that it was more expedient for him to play up his foreignness. Southerners were more likely to help him with directions and talk his ear off, slowly, about local happenings if they perceived him as a temporary irritant rather than a potential fellow citizen. Kim’s method for getting by in the South was thus to strategically orientalize himself, to “conform to the role of the stereotyped Asian both in my field work and in all other aspects of my life.”

It’s that “all other aspects of my life” bit that gets me, how someone can learn to flourish in a place without ever integrating into its fabric. Although Kim would spend more than three decades in the South before returning to Korea; although he raised his children here; although he owned property in the South, presumably paid taxes to a Southern state, and taught a generation’s worth of Southern students at UT Martin, where he was a professor of sociology until 2001, Kim never came around to seeing himself as a Southerner. It was like his time in the field began the moment he came to the South and didn’t finish until he left it: a thirty-six-year study completed by one “nonimmersed Asian ethnographer.”

I’ve been trying to remind myself on this latest Southern journey that my life and project are not the same as Kim’s, even if both of us link the South in our minds to a field both abstract and real. He stood outside or above it, his field site, trying to master its conditions. I’ve long wanted the opposite: to have the field master me.

Perhaps what I’m delineating is just a generational difference. Kim is my parents, or at least the stereotyped version of them I’ve constructed for easy consumption (terse and hard-working neo-Confucians, unconcerned with social justice and connected always to the old country), while I am their offspring, equally troped: this flighty layabout overfull of misplaced identifications; this second-gen wandering heart desperate to belong.

It seems too direct to ask my parents if they feel like Southerners now, thirty-five years after my father’s arrival. The answer, I fear, is liable to be yes and no at once. My mother tells me that when she moved here, she didn’t really consider how Tennessee might be different from anywhere else in America. And yet being here has changed her. “I think mostly in English now,” she tells me. It took many years for that to happen, but now the sounds in our minds are the same. I ask her if she found it difficult when I was young to communicate with me, a no-brainer kind of question that right after I say it makes us both laugh. “You think it’s hard?” she says, turning the question back on me. I lie and tell her I don’t remember.

Kim reports meeting someone like me in the course of his fieldwork, a Korean American born in the South named Wilson that Kim chastises as only a disappointed parent can. “He appeared Oriental, but knew nothing about the Orient.” And yet this young, oriental man, Southern drawl and all, could also not pass muster as Southern. By the Asian anthropologist’s standards, Wilson was a cultural mongrel lacking any “clearcut identity,” a con artist who didn’t even know he was running a con, this “marginal man belonging nowhere.”

It would be easy for me to compare my own Asian Southernness to bad improv, a mug’s game of representations in which what I’m taken for is rarely what I am. Due to the legacy of redlining, my public school and the tony suburb it served were both overwhelmingly white (Black Knoxvillians all lived in North or East Knoxville and attended schools we suburbanites disparaged as “inner city”). So, yes, what Asians there were in Farragut did stick out, and there were times when I thought of us, me and all the Asians I knew, as propertied squatters with no valid claim to this non-Asian place—a place I had the misfortune of loving as much as I did.

Still, it’s important for me to note that my own Asian identity did not form inside of a vacuum. My parents were early members of the East Tennessee Chinese Association, founded in 1992, and through that association’s various functions, had introduced me to other Chinese immigrants and their kids, some of whom have remained my lifelong friends. The things that bonded me to my fellow Chinese Knoxvillians were not just the strong nuclear forces of race and class and city. It was the baroque specificity of any scene within a scene, all these things I thought no one outside of our tiny East Tennessee x China enclave could understand, things like our aunts smuggling over seeds from Zhejiang; our mothers’ late nineties traffic in VCR tapes, all of Michelle Kwan; or that sigh of relief some of us breathed when it turned out we sucked at violin. It was the lopsided satellites on our porches that gave our visiting grandparents’ access to CCTV, and the better than passable Sichuan restaurant known as Hong Kong House, RIP, which used to sit like an MSG-laced beachhead by Tennessee’s first official state road. It was the miasmic, soul-crushing boredom of Sunday Chinese School weighed against the ethnocentric delights of parties we poopooed to our white friends but secretly relished. It was the magnificent sprawl of those parties, the pool of slip-on shoes at the door, the potluck contributions that deified their casserole containers, the mellifluous blend of Mando-pop karaoke and Super Smash Bros. Melee. It was the dads getting trashed at the weiqi table as the moms counted cards in the kitchen. It was learning the rules to all our parents’ games, but still sticking to Spades instead.

It was also the fact that one day we’d all leave. Whatever this milieu of ours was, it could not be reconciled with where we were, for where we were was in the South. I remember a night right after graduation when I took all my Asian friends with me to the field. We dragged a bunch of hay bales together into a circle, piled all our homework from AP Physics and AP U.S. History and AP Calculus in the middle of that circle, and then we set our homework on fire, because there was a lot of it, and the A’s we’d made no longer mattered. I don’t know what everyone was thinking that night at the bonfire of nerd vanities, but I’m pretty sure it had something to do with how we’d all be gone by summer’s end, off to some college north or west of here. This field in the South could not be ours. This field in the South had been caked on in stygian layers, sedimented in stories of decrepitude and succession, in histories always on the edge of forgetting and Southern people laid low by the weight of their benighted land. We would not be those people. We would be fleet of foot, pecunious. We would run until our yellow and brown bodies were lighter than Southern air, air that everyone knows is heavy.

But that’s only half of the story, the half I’ve been too eager to tell. In all my years of practicing wushu, the move I most wanted to master was called an aerial, a cartwheel performed in midair. I always started the move perfectly, my legs tossing up above me, my arms and shoulders relaxed as I somersaulted into flight. Then something in me would falter. My eyes would make contact with the field below. My hand would shoot down to touch it.

In the town of Rocky Top, Tennessee, I walk past rows of trailer houses, each with at least two “NO TRESPASSING” signs posted. Rocky Top used to be called Lake City before the local council brokered a deal with an investor who wanted to build a water park nearby. The investor promised to sink $100 million into the project, but only if the residents of Lake City agreed to rename their town “Rocky Top” after Tennessee’s official state song. Following a legal skirmish with the estate of the song’s writers, Lake City succeeded at renaming itself Rocky Top—as in “Rocky Top, you’ll always be / Home sweet home to me”—in 2014. The $100 million dollar water park, however, has yet to materialize.

It’s the middle of a hot day, and even the children are sheltering in place. The Thursday special at the Vol’s Diner is catfish, and the antiques store with the native effigy out front just closed. I’m walking past a gas station, feeling light-headed from caffeine, when the thing that always happens starts happening to me. (I don’t mean “always happens in the South,” as these scenes do not discriminate by region.) “Hey,” says a youngish white man biking on the sidewalk, and I’m already crossing the street, hoping my dodge wasn’t too obvious.

“Hey you,” he says again. “Do you understand what I’m saying?”

I walk faster, and the man starts to follow me on his bike. “Motherfucker!” he yells now. “Motherfucker! Chink!”

I keep walking and say nothing, though in my head I’m thinking “fucking meth head” and “redneck piece of shit.” The man on the bike keeps pace with me.

“Go back to where you came from!” “Motherfucker! Chink! Motherfucker! Chink!”

“Well, this is fucking stupid,” I say to no one but myself, turning off the street and breaking into a run. Without thinking it through, I grab a fist-sized rock off the ground and keep running, wondering if those long-ago years of wushu practice might finally come in handy. But the man soon disappears, the day rectified into silence. There is an empty baseball field in front of me, I notice, and a dead tree drawn and quartered by a chain link fence. I go to my car and just sit there for a few minutes, running the AC. I’m already berating myself for not dealing with the situation in a calmer or more confident way. Why had I immediately crossed the street instead of responding to the man’s greeting? Why had I been so quick to pathologize him, that “fucking meth head”? Why had fantasies of violence jumped so readily into my head?

I guess I’m more like Kim than I care to admit. Every time this scene repeats, I try to empathize with the opposition, to rationalize their actions as a neutral observer might, and in so doing, remove their barbs from my skin. I try and do this especially in the South, because in a deeply condescending way, I feel like I owe it to these sad people stuck in sad places, these Rocky Toppers plentiful in pride of place but scarce in everything else. And yet the bitterness in me is also very real, and very Southern. I may be fed up with myself for taking what amounts to schoolyard name-calling so seriously, but I’m even more fed up with them, these men and women who insist on begging the question in the most debasing of ways, these wrathful Southern revenants we honorary whites are supposed to handle with kid gloves or avoid. Why are we not extended, at bare minimum, the benefit of their avoidance? Why is it so hard, when they come calling, to stand where we are and just be?

I’ve been trying to leave the South for almost fourteen years now. Coming back is partly an obligation, a son visiting his aging parents. But truthfully, I feel out of sorts when I’ve been absent from the Valley for too long. My little sector of Appalachia is probably the one place on Earth where I can always tell when something has changed. There’s now a Kung Fu tea right next to Tennessee’s first highway, and a Pho 99 where a Stefano’s Pizza used to be. Near that pho place is Far East, a tiny Chinese grocer where I used to sit on a crackly leather armchair by the door as Mom picked out vegetables, sucking on a gratis Dum-dum. The kindly source of those Dum-dums is now dead (lung cancer, Mom confides), and so we do our shopping at a newer and better-stocked grocer called Sunrise. I always stop outside of Sunrise to read the latest notices pinned to the community message board. Today there are the usual advertisements for badminton lessons, citizenship lawyers, and language exchanges, plus a help wanted sign for Little Caesar’s with the tagline “JOIN THE EMPIRE” printed on it in all caps.

What’s also changed, to my sadness and surprise, is the field. Sometime in the last two years, the farmer sold the land and developers swooped in. The neighborhood will be called “Ivey Farms” when it’s finished. People will live there, and not just in their minds. They will lead lives not unlike the one that I led when I was growing up here, which is to say they will need their own outsides.

I must go and see it, obviously, the field before it’s no longer itself. It looks rather small with freshly paved roads circumnavigating its heart. Much of the ground cover has been stripped away to reveal the land’s livid, red insides, from which bulwarks of wood, soon to be houses, now rise. I think back to all the hours I spent here as a kid, how the field that wasn’t mine still conferred to me a sense of place. I learned my cardinal directions from sitting in that field and adopting its orientation. To the east were always the Smokies, to the west a woodland masking the interstate. My north was a new neighborhood, my south the neighborhood where I still dream. I don’t want to leave yet, but there’s not much left to see. I consider taking a few tufts of grass with me as a keepsake, but that would be morbid, I think, like shaving hairs off a corpse. As I cut back across the dividing line which separates my parents’ neighborhood from the field, I notice I’ve brought a bit of the field back with me, a few grams of Southern soil, pressed into my soles, that I leave behind me now as tracks.

To walk around with a vestigial geography in the mind, to feel shackled to a place whether you want to be or not: these are feelings an Asian Southerner gets from both sides.

Maybe the question is actually less complicated than I’ve made it out to be. You’re either from a place, or you aren’t; you’re Southern, or something else. I haven’t lived in the South since I turned eighteen. Ergo, I’m no longer Southern. What helps me undo this bind is the fact that so much of Southern identity is about missing a place from afar. This is a feeling many Asian Americans are also familiar with, even if the homes they pine for lie further east than Tennessee. To walk around with a vestigial geography in the mind, to feel shackled to a place whether you want to be or not: these are feelings an Asian Southerner gets from both sides.

This is also how I know that an Asian South does exist. I miss it. It’s as simple as that. All the glimmerings of that hybrid strata—the humidity, the cicadas, the scallions bunched up in the yard—and all the habits of mind and body these glimmerings sustain, they’re real. My father likes to talk about how he wanted to be an artist, too, when he was young—not a writer, but the kind of artist who sketches people in the park. He’s very glad he didn’t try to go through with that plan, the path of “crazy people,” he says. But now that he’s older, he’s gotten back into picture-making, using cameras instead of a pen. “I don’t think you could take a picture like this anywhere else,” he says of a heavily-edited image he’s just framed. The picture shows a forest in the Smokies from above, in autumn time, the foliage washed in ruby-red. Dad has affixed a stamp-style yinjian, or signature, to one corner, indicating that this Southern image is his. “Doesn’t it look just like a Chinese painting?”

As for my old dog, he coordinates his dying with the cicadas. By July, they’re all gone, and I’m reading a pamphlet from the pet crematorium warning me to avoid stewing in this “deafening silence.” Mom asks me what I think we should do with the ashes. I tell her we should scatter him in the field before its new tenants move in. When we try and take him out of the urn, though, the lid of the vessel is sealed. “Let’s just leave him on the porch then,” Mom says. He was sleeping there when he passed.

Excerpted from Take My Name But Say It Slow: Essays by Thomas Dai. Copyright © 2025 by Thomas Dai. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

This selection may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.