“If I could do it with an iPhone and 50 quid, I was making this film,” says Rich Peppiatt about his award-winning feature Kneecap.

The Irish hip-hop “print the legend” biopic on the Belfast-based rap trio — boasting Michael Fassbender among its ensemble — is a far cry from iPhone quality, and has taken the indie film world by storm.

Peppiatt’s Irish-language film, riddled with expletives, hallucinogenics and baton twirling mischief, swept up at the British Independent Film Awards in December and on Wednesday, scored six BAFTA nods, including for best British film and outstanding debut by a British writer, director or producer. It makes Kneecap the British Academy’s third most nominated debut film ever and Peppiatt the most nominated debut director in BAFTA history. It’s been no surprise to anyone that the movie is Ireland‘s Oscar submission for best international feature film this year, too.

Peppiatt can list journalist, stand-up comedian and advertising boss among his past endeavors (“I’ve lived a few lives”). When he saw something in band members Naoise Ó Cairealláin, Liam Óg Ó Hannaidh and J.J. Ó Dochartaigh, playing themselves in the project, he had a vision. “I think that people could see it in my eyes with Kneecap,” Peppiatt tells The Hollywood Reporter off the back of his BAFTA success. “That I meant it this time.”

The filmmaker has been dabbling for some years in the industry but has never had a project green-lit so swiftly. Everyone who came aboard Kneecap (later acquired by Sony) understood it was something special: a film deeply entrenched in Ireland’s political landscape and empowering for those who saw themselves reflected in it.

It’s a film that also upends the music biopic genre — one that Peppiatt calls “tired.” Instead of taking a fond — and usually sanitized — look back at the career of a well-known artist, Kneecap does the opposite: it chronicles the rise of veritable unknowns (playing themselves, no less) in a gritty, raucous romp that is anything but sanitized.

The movie follows the three band members on the up in Belfast, Northern Ireland, causing ripples (more like waves) wherever they go. For the first time, the people of Belfast have been presented with an impeccably-made film about three musicians rapping in their native language. It’s meant a lot to those residents, as well as the director himself, who made Belfast his home seven years ago.

A year after moving over, he came across a band playing a local gig. “On stage, they had this real fiery presence,” Peppiatt recalls. “In a world that’s very PR and packaged and safe, increasingly in terms of music, they were different. I just thought, yeah, I’ll take the bet that these guys are going to get bigger and grow, and I want to be there for the journey.”

Peppiatt opened up to THR about bringing Fassbender in as Irish Republican Army (IRA) member Arlo, making a film on Northern Ireland’s strained political terrain as a — wait for it — Englishman, and putting out into the world the riskiest, most daring version of Kneecap possible: “What I would hate is to have shaved off all those edges and be lying in bed six months later because the world had shrugged its shoulders and I’m thinking, ‘What if I’d really swung for the fences?’”

Rich, congratulations are in order. You’ve picked up six BAFTA nominations this week.

It’s felt like a very long time since the film premiered. Having never been in this situation before, it’s about a year later and you’re still very much in that machine of promotion. I’m off tomorrow to the German premiere. And they’ve actually dubbed [Kneecap] in German. A film all about the Irish language, dubbed into German. I don’t know how that’s going to work. But yeah, we’re performing far beyond what our expectations were. Anyone who makes a low-budget indie film and expects to be in BAFTA and Oscar conversations is a bit of a wanker. We’re just delighted that the film has resonated as it as.

How was it receiving the news of your BAFTA nominations?

I try and live life at a seven, which is not to get too excited about things and not to get too down about things. It’s been good news ever since, or even before, the film premiered. Going to Sundance but also even in the development. I’ve had a few films that I’ve tried to get made in the past and fallen at the final hurdle. But Kneecap was always blessed. Everywhere we went to ask for money, it was green light, green light. I’ve never experienced that. I kept double-checking: ‘Did you just say yes?’

What was it about this project, this band, that drew you in?

I think it’s such an out-there idea, a band playing themselves. The music biopic is a genre which has a certain popularity, but I also feel it’s very tired — it’s [often] looking back with rose-tinted spectacles at the career of someone who’s dead or nearly dead. It just felt like it had been done a million times. Was there a different way to do a music biopic and could you do it the opposite way around, so you’re basically following a band on the up in real time? Then I met Kneecap, and I was just like, I’m gonna put my eggs in this basket.

The band members play themselves in ‘Kneecap.’

‘Kneecap’

Kneecap were just a local band at the time that I met them. And [local bands] mostly just fall away, they don’t get any better, they break up. But I just had this feeling that Kneecap was something special. They were overtly political, raw and authentic. There was something so fresh about them, something that I hadn’t really seen since, something like Rage Against the Machine back in the ’90s. In a world that’s very PR and packaged and safe, increasingly in terms of music, they were different. I just thought, yeah, I’ll take the bet that these guys are going to get bigger and grow, and I want to be there for the journey.

How was it taking that vision to the people with money? It sounds like it was relatively — by industry standards — easy to get made.

To be honest, I’m still surprised that funders got behind it because it wasn’t like I was a seasoned filmmaker. But someone once told me: ‘It’s all about securing talent,’ right? That’s really what this [industry] is about. And I think people started to see that Kneecap were a really interesting talent and I just had a very, very close relationship with them. Our relationship is far more than a normal director-actor one. They’re round my house all the time, they’ve babysat my kids. They’re family. That trust we’ve built up over six years together probably informs their performance. Because when I’m asking them to do things, they trusted me to do them.

Were there any concerns or risks you decided not to take?

The band were obviously concerned at times and go, ‘Do we look silly? Is this really what we should be doing as a band? What if it doesn’t work?’ There was lots of existential issues that could have come up. There was lots of difficult conversations, but we got through them. Naoise’s storyline with his mother absolutely mirrors what really happened. And while we were writing the script, his mother killed herself. That’s not breaking any confidences, he’s spoken about it himself, but that was the hardest thing.

I am so sorry to hear that. How awful.

Everyone thinks it was all fun and games, but we had an almost finished script, and then that happens. Having to sit down to have the conversation [and say], ‘Do you want us to change this script? Do you want to do the film at all?’ Naoise very quickly came back and [said] ‘I think it’s the best way to honor her, because this is the truth.’ But then imagine being on set and having to act with Simone Kirby, who’s playing your own mother and going through the emotional beats that you actually went through. The bravery of him, to pull that off. It was so hard for him. I think some people sometimes look at the film and go, ‘This must just have been a big orgy of fucking around.’ We took it very, very seriously. I’m a big planner of things. There’s over 1000 storyboards for the film. To get that real anarchic film feel and spirit, it took a lot of very, very boring planning work.

You mention talent being attractive to financiers — was it easier when you got Michael Fassbender on board? How did that casting come about?

It was very, very late. People do think that we got Michael and then Michael managed to get the film green lit because he was attached. It wasn’t that at all. The film was already happening and we needed to find an actor for that role, [someone] who spoke Irish. As most directors do, you go, ‘Who’s the biggest people that I might be able to find for this?’ And there’s only a handful of what you call top-tier Irish actors who can speak Irish, and Michael was one of them. Michael played Bobby Sands in [Steve McQueen‘s 2008 film about the 1981 Irish hunger strike] Hunger. That’s such an iconic film for the people of Belfast, there’s so much love for Michael and certainly the band had a lot of love for him. It was like, ‘Well, let’s go for him first.’

Ó Cairealláin and Fassbender in Peppiatt’s film.

‘Kneecap’

There is this idea that actors are really difficult to get and they won’t do your little film. But I think bigger than that, from knowing actors, is that they just want material that they connect with and enjoy and feel like they can bring something to. And there’s not a huge amount of that around in the middle-of-the-road stuff. I think we caught Michael at an interesting time in his career. He had been motor racing for a few years, he was starting to fill his calendar with acting stuff. He will tell you himself that playing Bobby Sands was probably his favorite role, the one he’s connected with the most. And I think that the opportunity to reprise a role that is almost the guy who was in a cell next to Bobby Sands, but didn’t go on hunger strike, right? That was the conversation I had with Michael. Arlo, your character, that’s where his anger and his obsession with the cause comes from, that a place of guilt that he didn’t give the ultimate sacrifice.

I have to confess that I wrongly assumed you were Northern Irish. It was only after seeing the film and doing my research I found out you’re an Englishman. This is a deeply political movie, and there’s a gap in our knowledge — as English people — when it comes to Irish history and the Troubles. So I’m beyond curious as to how you became an expert.

You’re completely right. I grew up around Staines, West London, the Heathrow area. And you go to school, you do a chapter on Irish history and then you move on to the Tudors or something. It’s a bit, ‘Oh there are some terrorists, and the British government kind of dealt with them.’ And you don’t really think [about it] because you’re a kid. I had never even stepped foot in Ireland until I was in my mid 20s, when I met a girl who was from Belfast, and we started dating. She was from West Belfast, Andytown, in the heart of West Belfast and the madness of things. Me going out to meet her parents and her family and her three, 6’5″ brothers. That was fun. [Laughs]. We only held hands.

It was a re-education for me. It was really eye-opening. It really was that thing of, oh, I get it. Fuck. I didn’t realize we are the bad guys. And, you know, my father-in-law now and their family have been through some of the worst things through the Troubles. They really suffered at the hands of the British Empire. And to welcome me into their family like they did, with no judgment upon me… Seeing it as the British state and I was just an individual, was something that really touched me. Given some of the things that they’ve gone through as a family, I would have found that quite difficult — to hear that accent round your house, knowing that they were the people kicking your door in and putting guns to your head and beating you up.

You’re an honorary Belfastian.

When I moved to Belfast, when I started having children about seven years ago now, I’ve always felt welcomed around West Belfast, the very Republican area. I’ve always drunk in the pubs and found it to be a very welcoming place to me. Now, admittedly, I have family connection there and I’m sure that helps. I’m not just some English fella off the street. But people have this idea that if you’re English, you’re suddenly going to get your head kicked in because you go into these Republican enclaves without having been through my experience. The same with Kneecap — people think, ‘these hardcore Republican rappers, they hate Brits.’ And it’s like, they don’t hate them that much. They spent six years working with one, right?

It really is this distinction between the British state, the British Empire and what that has done — not just in Ireland, but around the world — and the British people. I’m really happy — that’s a place that’s given me a lot. Belfast is my home. It’s where my family are. To be able to make a film that’s really connected, first and foremost, with the people of Belfast, and particularly in West Belfast, and to be able to walk down the street and people congratulate you and go into pubs and people want to buy you a pint, that’s really nice. It’s nice to feel like you’ve done something where the people who it represents really feel that it represents them truly, right? As a filmmaker, when you pull that off, that’s bigger than awards to me.

Six years you’ve spent with those boys. Can you talk a little about the decision to cast Liam, Naoise and J.J. as themselves?

There was never really an idea to do it otherwise. Part of that was because if you’re taking a band that no one really knows, and you suddenly cast Barry Keoghan in the role of one of them… He’s more famous than the band. I think conceptually, it would never have worked, right? If you’re going to take an unknown band, I think you have to try and work with them, to turn them into actors. That was always part of the challenge: could we do that? But when I met them, that first year was really the world’s longest interview. It was just hanging out, drinking, getting to know each other, and really trying to tell stories. There’s stories people tell you after three pints, and there’s stories people will tell you after 15 pints at 6 a.m. in the morning. And I needed those stories. So that meant a lot of late nights, a lot of partying.

I embraced who they were — I learnt the [Irish] language. That was a big thing. I did night classes. I think that was very important to them, to see me trying to embrace their culture. When you’re with three people who speak Irish, when they’re together, you’re very conscious that they have to shift language to suddenly be speaking English. You’re now an imposition. And so whilst I’m not fluent, I think that they appreciate when you’re making an effort to at least be able to ask, ‘Who needs a drink?’ in their native language.

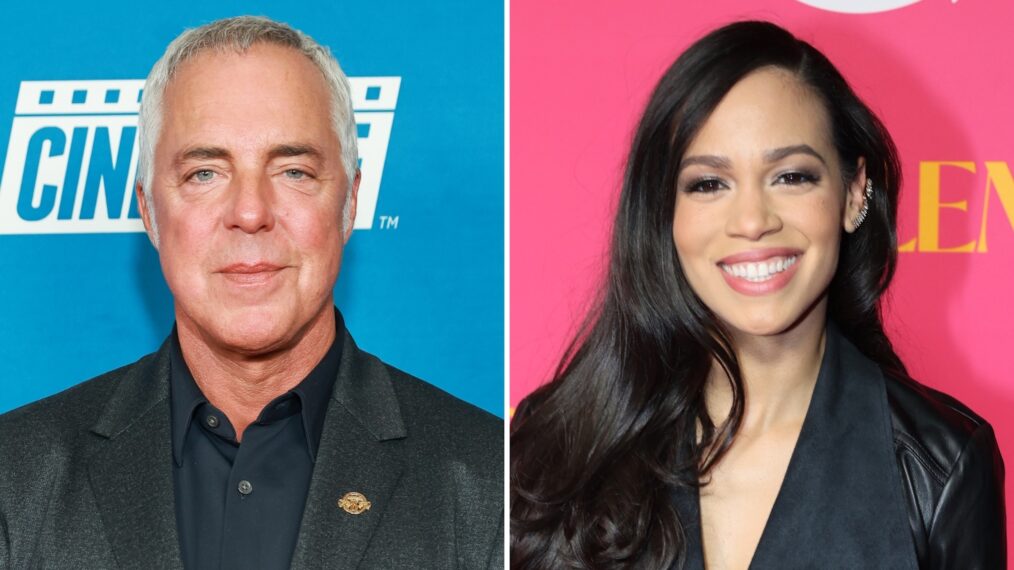

‘Kneecap’ director Rich Peppiatt (left) with his cast at the BIFAs in Dec. 2024.

Courtesy of Getty Images

Kneecap is about the political sentiment in West Belfast, but it’s also about a deep understanding of the Irish language’s right to exist in Northern Ireland.

When I first met Kneecap, they were playing a gig in a bar called Limelight [in Belfast]. On stage they had this real fiery presence. But what was more impressive than them was the fact there was probably 800 young people in the crowd who knew every word that they were rapping in Irish and were shouting it back to them. And for me, the revelation that there was this young, vibrant Irish language community in a place that, you know, legally, illegally, however you want to see it, is part of the United Kingdom. These people were mainly born in, ostensibly, the United Kingdom. That, to me, was quite a revelation. That contrasted with the political level: this fight for an Irish language act that had been pencil-pushed around different departments and things for years and years. The juxtaposition between what was happening at a political level and what was happening at a grassroots level felt to me, as a former journalist, very interesting.

I wanted to ask you about your past life as a journalist. How do you think that side of you helps — or even hinders — your directorial approach?

Journalism is storytelling, right? That’s the foundation of it. I don’t think there’s a huge leap. I think I’m always attracted to real-life stories. Things that have a kernel of reality in them. Perhaps that is the journalist in me. But after journalism, I did stand-up comedy. I then had a production company doing advertising stuff and branded content. So I’ve lived a few lives. But through everything I did, the dream was doing what I’m doing now. I was always trying to work my way there. I was approaching 40 and I said to myself at 34, I need to get my first narrative feature done by the time I’m 40. If it doesn’t happen by then, I don’t think it’s going to happen.

I think that people could see it in my eyes with Kneecap. That I meant it this time. I wasn’t going to take no for an answer and one way or another, I was going to make this film. If I could do it with an iPhone and 50 quid, I was making this film. And when the money was there, I was then very determined that I was going to make the film that I wanted to make. I was going to put everything that I enjoy in. I was going to make it for me as much as anything, because failure is something that I could accept. I could accept if no one wanted to watch the film. But what I couldn’t accept was letting maybe too many voices in and letting the film get watered down from what it is, which is very authentic, very raw and very risky in places. I don’t mind them not working — what I would hate is to have shaved off all those edges and be lying in bed six months later because the world had shrugged its shoulders and I’m thinking, what if I’d really swung for the fences? What if I’d really gone for it and just tried to make something different and something that really reflected me as a filmmaker, would it have been a different result? So, yeah, we took the risk, and we’re obviously ecstatic that it’s paying off.

Paying off is an understatement. With such a friendly and fluid dynamic between you all, what was the creative behind-the-scenes of Kneecap like? Were there any fall-outs?

Making a film is like running through a field of poppies. We’re trying to do a lot in a little amount of time with not enough money. There’s always tensions, there’s always difficulties. I had a very, very good relationship with our [director of photography] Ryan Kernaghan, who I’ve never worked with before. It was a big risk for me. I needed to get an Irish DOP rather than a DOP that I knew from London. Ryan really embraced the madness of it. And I don’t think any other DOP could have made the film that we made. There were always difficulties along the way, but I’m still friends with most people involved. [Laughs.] Not everyone, but I won’t tell you who.

.jpg)