One of the greatest pleasures of my reading life this past year was consuming what I’ve been calling “snackable” books—books you can read in one or two quick delicious sittings, which is not to say they lack nutritional value. I usually find that I wish I had more book left by the time I reach the end, but I also know that their brevity is part of their power; that the desire to keep reading is partly why I like them so much.

A few stand-outs in this category: The English Understand Wool by Helen DeWitt, Woman Pissing by Elizabeth Cooperman (I first learned about this book via Elisa Gabbert’s own annual year-end list from 2023; I later drew a comic about it for RHINO’s graphic issue); Claire Keegan’s Foster and So Late in the Day (my mother had been urging me to read Keegan for the last couple years; what made me finally do so is that these two were chosen for my book club—I was relieved to find out that the hype, in this case, was warranted); Clarice Lispector’s Hour of the Star, and a small zine/chapbook called Painting and Consciousness by an artist named Jordan Wolfson. I also quickly blew through Sigrid Nunez’s The Vulnerables, my first read of 2024, which I’d received for Christmas. I went in knowing nothing, armed only with the knowledge that I’d loved her two previous novels, The Friend and What Are You Going Through—which is to say I had no idea it took place over the pandemic, a fact the official summary sneakily (and smartly) elides.

A few stand-outs in this category: The English Understand Wool by Helen DeWitt, Woman Pissing by Elizabeth Cooperman (I first learned about this book via Elisa Gabbert’s own annual year-end list from 2023; I later drew a comic about it for RHINO’s graphic issue); Claire Keegan’s Foster and So Late in the Day (my mother had been urging me to read Keegan for the last couple years; what made me finally do so is that these two were chosen for my book club—I was relieved to find out that the hype, in this case, was warranted); Clarice Lispector’s Hour of the Star, and a small zine/chapbook called Painting and Consciousness by an artist named Jordan Wolfson. I also quickly blew through Sigrid Nunez’s The Vulnerables, my first read of 2024, which I’d received for Christmas. I went in knowing nothing, armed only with the knowledge that I’d loved her two previous novels, The Friend and What Are You Going Through—which is to say I had no idea it took place over the pandemic, a fact the official summary sneakily (and smartly) elides.

Throughout this whole past year I’ve been reading John Berger’s astonishing collection Portraits in chunks at a time; each essay is about (or inspired by) a particular artist, and the book is organized chronologically so that the first essay is about the Chauvet cave painters and the last essay is on Randa Mdah. I’ve been flipping to different artists at random, whenever I need to wake up my mind and strengthen the connection between my eyes (image) and my brain (intellect). I recently added his book Landscapes to the mix as well. Whenever I read John Berger, I think, why am I not always reading him?

I have also, since August, slowly been reading Swann’s Way, a few pages at a time. Some mornings I read two pages, sometimes four, sometimes ten. You would think this would be a bad way to read a long and meandering book (and maybe it is) but so far it is working…(also I feel like Proust SHOULD take a long time!)

For poetry, I never feel like I read enough, though this year I read and really enjoyed Mary Ruefle’s The Book, Diane Seuss’s Modern Poetry, Madeleine Craven’s Pleasure Principle, Megan Pinto’s Saints of Little Faith, Victoria Chang’s With My Back to the World, Leigh Lucas’s Landsickness, Elisa Gonzalez’s Grand Tour, Ariel Yelen’s I Was Working, Janet Foxman’s Disposable Camera, Summer Farah‘s I Could Die Today & Live Again, and Emilia Phillips‘s Nonbinary Birds of Paradise, among others. A big highlight was Margaret Ross’s Saturday, which I’d been eagerly anticipating, and which just came out this fall.

Not technically poetry but I also finally read Louise Glück’s book of essays, Proofs & Theories, which I first obtained in grad school and have only read in bits and pieces over the last ten years—this past October I finally sat down and read the whole thing straight through. Also not technically poetry but I loved Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries, which comes to mind here because when I attended her reading at the Booksmith in San Francisco, someone asked her what genre best described her book, and she said she considered it to be fiction, nonfiction, and poetry—a satisfying defiance (or abundance?) of categorization I wish more books were “allowed” to traffic in.

Not technically poetry but I also finally read Louise Glück’s book of essays, Proofs & Theories, which I first obtained in grad school and have only read in bits and pieces over the last ten years—this past October I finally sat down and read the whole thing straight through. Also not technically poetry but I loved Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries, which comes to mind here because when I attended her reading at the Booksmith in San Francisco, someone asked her what genre best described her book, and she said she considered it to be fiction, nonfiction, and poetry—a satisfying defiance (or abundance?) of categorization I wish more books were “allowed” to traffic in.

I moved from California to New York this past summer, and in the wake I read and heartily underlined The Beauty of Light: Interviews with Etel Adnan. I acquired it shortly before packing up my apartment in Berkeley, maybe partly because I was thinking of Adnan’s paintings of (and writings about) Mount Tamalpais, a place and landmark I knew I would soon be nostalgic for.

Other stand-outs from the year:

Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything, which I fittingly devoured a few months before I moved to New York.

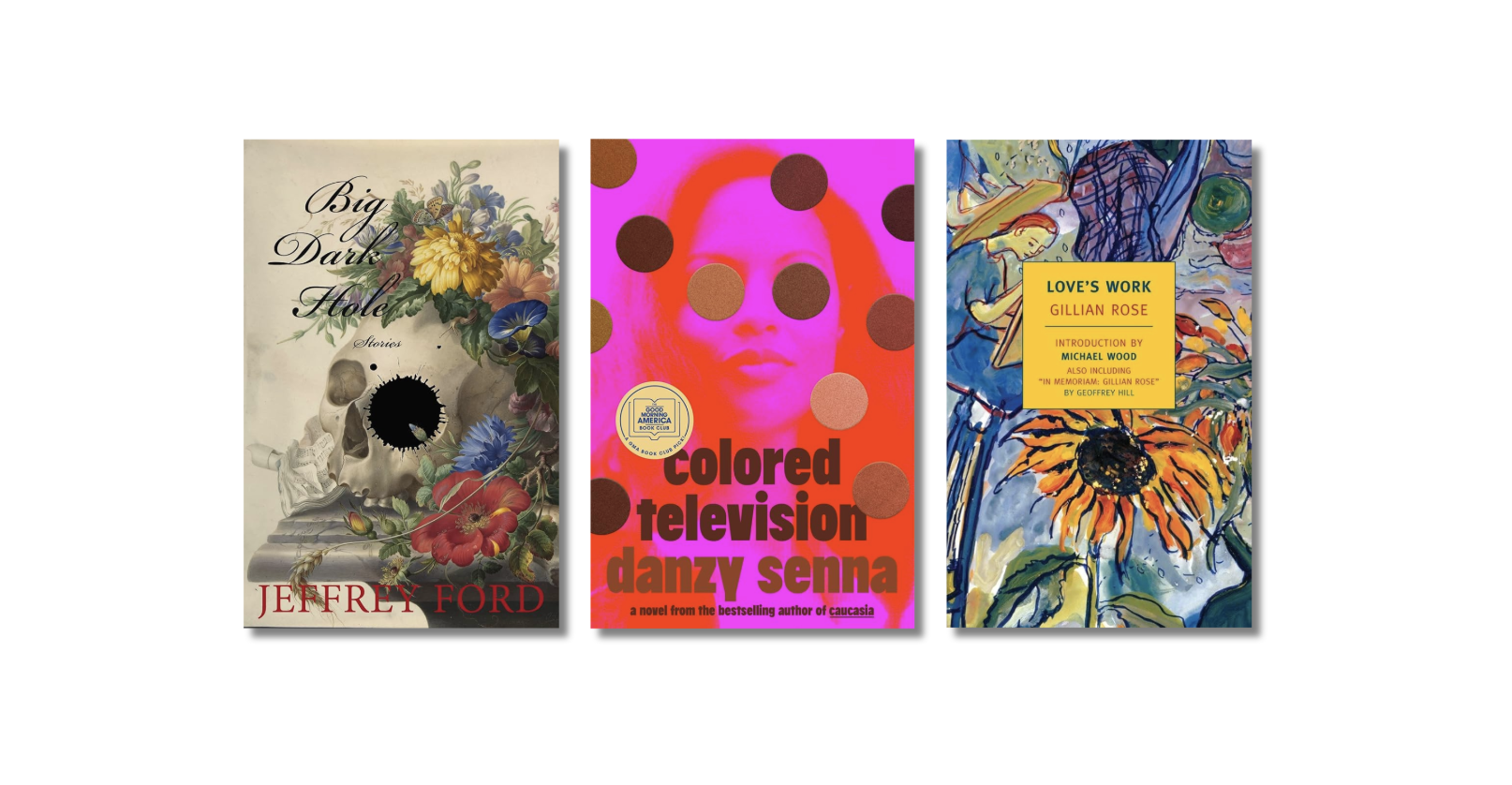

John Williams’s Stoner—I was a little skeptical of this book going into it, partly because of recent hype and partly because the synopsis made it sound so dour, but it turned out to be one of the most moving books I’ve read in recent memory (it is also a bit dour, which is fine).

Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed – This feels like a sneaky all timer—yet another one of the most moving books I’ve read in recent memory!! Lucky me.

Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip and The Children’s Bach – Garner is a fascinating writer to me because her prose has this deceptively informal quality, but in fact its casualness is highly controlled and precise—in these novels at least, she gives the reader only what they need to know, and the ensuing pace provides a sort of off-kilter foundation to the reading experience that also feels incredibly intimate. Also important: she is very funny.

Vigdis Hjorth’s If Only – A coworker at my first publishing job once asked me which writers I’d always read, no questions asked, as soon as their new books came out, and I was kind of stumped about how to respond. Ten years later this is still a question I think about all the time, and Vigdis Hjorth is one of my answers.

Rita Bullwinkel’s Headshot, about girls competing at a boxing tournament – I loved the way Bullwinkel captured the interior consciousness of the girls as they fought one another, as well as how she’d leap forward in time to show us who the girls will become as non-boxing adults, simultaneously raising and lowering the stakes of said competition. (I’ve been keeping track of my reading this year in an Excel spreadsheet, and in my notes for this one, I wrote simply: “Women in sports!!!”)

In nonfiction I also particularly enjoyed:

Emmanuel Carrère’s Yoga, which I actually thought was a novel for the entire first half, only realizing it was a memoir upon reading Elvia Wilk’s own Year in Reading from 2023. (Does it matter though? I love novels that read as memoir and memoirs that read as novels.)

I loved and learned a lot from the fascinating structures of Sarah Viren’s To Name the Bigger Lie and Shze-Hui Tjoa’s The Story Game, and I was equally enlivened by the essays in Elisa Gabbert’s Any Person is the Only Self for the way they chart all the twists, turns, and adjacencies of their subject matters.

I’m currently midway through Percival Everett’s novel Erasure (so much more satisfying than the film adaptation, which I liked), as well as Erica Van Horn’s Living Locally, which is comprised of excerpts from the daily journal she kept over the course of five years living in the Irish countryside. I picked this one up at random at Point Reyes Books because I was drawn to the cover, and as I was flipping through it, bookstore owner Stephen Sparks walked by and said it was great, at which point I needed no further convincing. It’s also, I’m finding, the perfect book to read on the subway—Van Horn’s anecdotes of rural Irish life, like waking in the middle of the night to find a bunch of cows outside her door, or falling into a pit of despair due to the constant rain, are completely transportive when crammed into a train car with strangers and hurtling beneath the ground of a big city. Her accounts of living among her neighbors in their rural community, the observations they draw about the state of their society, economy and country from noticing the small shifts of their everyday experience, feels like a refreshing thing to read right now, reminding me that the world starts right where we live.

And, because it’s not the end of the year just yet, I have these next up on my list and waiting for me on my bedside table: Isabella Hammad’s Recognizing the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative, Katie Peterson’s poetry collection Fog and Smoke, and Ayşegül Savaş’s The Wilderness.

![[Spoiler] Shot, Wes vs. Csonka [Spoiler] Shot, Wes vs. Csonka](https://www.tvinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/fbi-international-408-vo-wes-1014x570.jpg)