Several directors of photography are in Oscar contention this year after reteaming with a director they had worked with previously. Some lensed $100 million-plus epics, while others shot films with tighter budgets. Whatever their situation, six of this year’s leading DPs gathered on Zoom in October for THR’s annual Cinematographer Roundtable to discuss their paths into the profession, their stance on VFX and the biggest challenges they faced on their projects this year.

The six roundtablists were Maria’s Ed Lachman, who previously worked with Pablo Larraín on El Conde; Gladiator II’s John Mathieson, who lensed the first movie as well as others from Ridley Scott’s filmography; Wicked’s Alice Brooks, whose collaborations with director Jon M. Chu include In the Heights; Emilia Pérez’s Paul Guilhaume, who shot Jacques Audiard’s Paris, 13th District; Dune: Part Two’s Greig Fraser, who, of course, also shot Part One; and Nickel Boys’ Jomo Fray, working for the first time with director RaMell Ross.

What was your introduction to the profession, and what made you recognize and appreciate the role of a cinematographer?

ALICE BROOKS I grew up in New York City with a playwright father and a dancer and singer mother. And we were super poor. We lived in a one-bedroom tenement apartment, 300 square feet, with the bathtub in the kitchen. My mother put my sister and me into child acting when I was 5 and my sister was 3. When I was 15, I had my last audition, for a movie called While You Were Sleeping. It was a Sandra Bullock movie; I knew in my heart I hadn’t gotten the role. I said to my mom, “I don’t want to be an actress. I want to be a cinematographer.” And she said, “I know.” And I looked down and there was this little gray and white feather. I still have it.

I applied to film school at USC and my mom made me walk my application in, and she said, “We don’t have the money to send Alice here, but she deserves to go here.” And two weeks later, I had a full scholarship. Back then I thought that was the best day of my life.

JOMO FRAY My journey, similar to Alice, started really young. I have a picture of myself behind a video camera telling my parents at age 7 that I wanted to be a filmmaker. I grew up constantly changing my ideas, like, “I want to be a scientist,” “I want to be an astronaut.” I want to be this. I want to be that. And I remember thinking I want to do film because that way I can live the life of a scientist for three months and then think about the life of an astronaut for two months. It felt like this ultimate hack somehow.

I remember when I first saw In the Mood for Love [which is in several languages] and calling my mom and saying, “Fifteen minutes in, I stopped reading the subtitles and I was just completely enraptured by the images, because I feel like they were transferring emotion into me.” I think it was at that moment that I specifically became obsessive about image making.

JOHN MATHIESON I drifted into it. I moved to London and found other people who were mucking around with cameras. I went from there — someone lending you this, someone lending you that. I couldn’t get into the union; they were horrible, bigoted, Rupert Murdoch-reading, nasty people. So then I did music videos. You didn’t have to have a union ticket to work on those. Everyone loves the movies, but then you notice the photography. You remember if a film’s still staying with you three days later, but you don’t really know why. That’s when it changed, I suppose. I’m in my mid-20s and I got on board with music videos, and one thing led to another and I ended up in drama.

PAUL GUILHAUME I grew up in Paris, France. My mother was an art teacher, but she was also taking photos. Very early, I wanted to do cinema. There was this line producer that my parents knew, and one day — I was 14 — she told me, “You want to do cinema? What do you know about it?” And she told me about the journey of a director preparing a movie, meeting directors, writing the script, et cetera. And one of the jobs was meeting this person and talking about the look of the film and going to the museum and saying, “The film could look like this painting.” I thought, “I want to be this person.”

ED LACHMAN I grew up with a father that was an amateur photographer, and I abhorred photography. I took the position that it stole your soul. I went to art school and I took a survey course in film appreciation. And it was Italian neorealism. It was a film by Vittorio De Sica, Umberto D. I was so taken with the film because it had sound, but it was basically a silent film. I realized those images just don’t get up there on the screen. I was always interested in the found image, so for me it was like you could put together images to tell a story.

GREIG FRASER My journey began not really knowing anything about the film business, but I started getting pretty good at photography when I was in high school. I also didn’t understand what a cinematographer for cinema was. I knew what a cameraman in the news did, but that wasn’t of interest to me. Creating art images was. It wasn’t until I joined a film photography studio that I actually saw a cinematographer work and realized that it was the best of both worlds.

At the start of one’s career, one might not have options about who you want to work with. But since establishing yourselves, how have you picked who you work with and who you want to work with again?

LACHMAN Well, they hire us. You just build a familiarity with that person. Generally, there’s a reason why it worked out on the first film, so they want to work with you on the second film.

FRASER But Ed, how would you choose a film with a director that you haven’t worked with before? Everything that you do is significantly different from each other.

LACHMAN With Pablo, all his films were totally different visually. Not all directors are visual, but if you have the ability to work with someone that’s visual, who understands what your contribution is, that’s going to excite you. And generally, when you work with someone you connect with, you want to continue that. Certain directors use cinematographers as they move up the scale to bigger films, so they want to work with the next biggest DP. But the directors that everybody here works with are already very established in their own visual language, so they know why they want to work with these cinematographers.

MATHIESON [Ridley Scott] chose me, as simple as that. I’d like to say that you can choose. I don’t think you really can. There comes a point you can’t wait for something anymore and you have to jump. Before this one, I did a small film, but no one’s going to see that. They know me as the Gladiator guy. “Give me men in leather miniskirts!” I don’t want to do men in leather miniskirts anymore. I think [Ridley] has various projects he wants to do, but you get folded into what [you’ve done before]. So, yes, I do well, but it’s a curse. Everyone wants to be Ed. He’s got better hats than I have, for one thing. I admire his film diversity.

I don’t know. … This idea you choose the project is not really true.

FRASER But you can choose not to do it, John.

MATHIESON Yes, and there’s been plenty of that. I waited for months, even years, for people to make a film just to watch them dry up, and missed so many things because I believed that it would happen.

BROOKS I’ve known Jon Chu since USC film school, where we bonded over our love of musicals. We made a short musical film called When the Kids Are Away, and his career took off, and we didn’t see each other for a few years. And then we started doing this little web series together, The Legion of Extraordinary Dancers. He always has believed in me, and I think someone who believes in you and trusts you and is able to speak the same language — this has been really lucky for me.

There are jobs I’d go in knowing a hundred percent I’m not getting the job. It was year after year of “no, no, no,” and then, one day, things changed and suddenly, Jon was at the point in his career when he got to make his own choices. In the Heights was the first movie I never interviewed for, and I didn’t interview for Wicked. Maybe we do get to choose some things, but the projects have to come to you.

Jomo, this was your first time working with RaMell Ross, who had shot most of his previous work himself. Was he very clear on what he wanted his film to look like?

FRAY Thinking about working with a new director, I want to work with someone who I’d love to dream together with. Maybe it’s a hot take, but I love signing on to a script that I can’t previsualize. Like, if it is beautiful to me as I’m reading it, I don’t feel like I’ll be truly challenged as an artist to do it because I’m already half of the way there thinking about what it could look like. I love taking on a project that is fundamentally going to be a challenge for me, not only as a cinematographer, but as an artist. For Nickel Boys, the entire movie is shot from a first-person perspective. When I was reading the script, I was like, “I don’t really know what that means.” We came up with this concept that we call “ascension perspective.” We would use “first person” with the crew so people could previsualize, but for us, it was the idea of this sentient image that was less concerned about what it looks like to see, but more what it feels like to see, and toward that, an image that’s just always tied to a real body, a real person with real stakes as they’re navigating, in our case, the Jim Crow South.

FRASER Jomo, would you say that you took away a lot from that process, having learned from that director, given that he’d shot his own stuff before?

FRAY Absolutely. He thinks about images in a totally different way, so our conversations always felt so fruitful. With this movie, it was a totally different relationship as a cinematographer, capturing an image from inside the scene. If Hattie, one of the characters, hugs the protagonist Elwood, it’s me she’s hugging physically.

Visually, how do you arrive at a game plan for the look of your film? Is the filmmaker asking you, “How do we make this happen?” Or is he telling you, “Make this happen”?

GUILHAUME It was a collective process of many people sitting in a room for many months, and in the end, you don’t know where the ideas come from. Emilia Pérez was first going to be a very gritty handheld film shot in Mexico, and we were talking about Amores Perros and someone else said, “Let’s shoot an opera onstage, and we’ll do a lot of lighting effects,” and the two projects gradually merged into one. We realized during location scouting [in Mexico] that the film would be very much to the ground, maybe too much, and the opera would be maybe not in the world enough.

Greig, I read that Denis Villeneuve wasn’t very prescriptive with how to lens the first film. Was that the case with Dune: Part Two?

FRASER We managed on the first one to get all the technicals sorted. On the one hand, it’s fantastic, but on the other hand, it also can sometimes make you confident that you’ve solved all the problems. Whereas, you know, if you’re making a film, as Paul just said, you’re constantly looking for what the film is. As Jomo just said, you’re constantly watching and trying to sort out what is this film we’re making. We knew what the film was because we’d made it, but actually we didn’t, and we were discovering it as we went. Denis definitely had some opinions about the choices we’d made on Part One. I discovered at the beginning of Part Two that he didn’t like the anamorphic lenses we were using, which is a really tough time to hear about that. When the film’s out, you’ve done it, and he came to me and said, “Mate, I just don’t love those lenses.” I was mortified because those lenses are my babies. I do stand by our choice to shoot anamorphic for some of the first film, but we didn’t shoot anamorphic for the second film because it didn’t fit the story where we were. I still have to get to the bottom of what about them he does not like.

John, does Ridley, at this point in your collaboration, still give you pointers? Or is he like, “John, you know what to do. Do it.”

MATHIESON Yeah, not much discussion, I’m afraid.

FRASER Was the process different on Gladiator II? There were so many years between them, John.

MATHIESON The only difference to me was filming digital.

FRASER But did he change his style?

MATHIESON I think he’s moved with the times and he’s made a lot of films between those two. He’s very prolific.

LACHMAN I know he used to go in the lab and time the dailies, even.

MATHIESON He never timed dailies for me. He likes digital — he likes to see the image instantly. I found an old thing on YouTube the other day and it was a making of Gladiator. He was a lot more active and a lot more around the camera when it was on film, and everybody else was too. They’d come to the machine and say, “What are you doing?” And I prefer that, because if something was wrong immediately after a take, everyone was there.

FRASER I thought you shot Gladiator II on film, but no — you’re telling us you shot digital.

MATHIESON There’s a lot of film in there. We had days of 5,000 extras last time; this time, we barely had 500. You can’t reshoot everywhere with lots of cameras because you don’t have enough background, but you can if you do it digitally. The first Gladiator was 50 shots of visual effects. I think it’s one of the reasons it stood the test of time: because there was so little CGI. This one has — I don’t know how many, but of course he’s embraced that now. He was suspicious of it before, which rightly he should have been. But we jumped from 50 shots to Kingdom of Heaven, which was 800, to I don’t know what this is. Thousands.

It seems it’s getting harder and harder to tell what is shot on camera versus what’s later added in VFX.

BROOKS The first Wicked has very little bluescreen in it. We shot on 17 stages across three different studios, and our sets were built fire lane to fire lane, floor all the way to the reds. Every single inch of every stage was used. Two of our sets were the size of four American football fields each, and we had four backlot sets. Jon, Nathan Crowley, our production designer, and our visual effects supervisor, Pablo Helman, and I all had a conversation very early on, maybe a year before we started shooting, that we wanted to do as much on camera as possible, that our goal was to make an Old Hollywood movie and not rely on visual effects. And of course we do have visual effects: We have visual effects characters, the animals. But I had real practical sets to light. Jon is a director who likes to be able to go in and shoot 360 degrees, and so I would pre-light every Saturday and Sunday. The sets were so massive that there was no other way to do it. There are people that have said to me, “The ceiling in the wizard’s throne room, how was the set extension on that?” There is no set extension. That is all real.

John, you have said that you turned down offers to lens Harry Potter’s last installments because you felt there would be too much greenscreen involved. Later, you said, “What an idiot I was,” after you realized there wasn’t that much at all. I was curious what your position is in terms of VFX versus practical in your films.

MATHIESON Harry Potter at the time was thought of as very VFX-heavy. But the standard way to make [a film like this], you have five stages. One’s green, one’s blue, and you go there for however many days it is, and then you get a movie. Ridley, like me, we got into this game to go around the next bend in the river. We wanted to go on location. He very rarely shoots in a studio. We had one studio scene in this film, which wasn’t really a proper studio, but a warehouse.

He builds on this old sort of Napoleonic, neoclassical fort in Malta, and Malta is made up of crumbling, rich tea biscuits, everything’s falling down the whole time, so you get this sense of decay. You don’t know how old things are, but the background is there. These are the walls of the old Napoleonic fort, there’s a big area and then in the middle of that, you put the Colosseum, some temples, the Forum, some palaces, and then they need to be topped up. But [the actors] walk into, essentially, Rome. It’s real. Rome’s one of the oldest cities as we understand it, so people know what it looks like, so you’ve got to get that VFX balance right. The first film, I don’t think he trusted the VFX. I don’t think he understood it fully, which was just as well. But I think one of the reasons it stayed with us is that it’s real. You have the sense of what it was like to be there. He really does worlds.

I’d rather shoot it on film, of course, but he won’t go back there. Look at the awards last year. Look at how many of those films were shot on film, and I liked them all. But he will stay digital. He will never go back. He likes that, and for this sort of filmmaking, it’s better suited. Undoubtedly. I don’t say I like it. Rather than bluescreen hell, I’d rather go to a yoga retreat.

At a time when the industry’s default, for cost reasons, is to shoot digitally, many of you still fight to shoot on film. Is that fight getting harder to win?

FRASER In my career, I’ve shot both digital and film. Film has a real special quality to it, and it does seem like the default for budgets and for filmmakers is to go with digital, which I think is a real shame. I wouldn’t say it’s getting harder to win. I think maybe it’s getting slightly easier to win because again, I think that digital has come full circle and film is starting to get back into the good graces of the accountants in the budget. But it is incredibly important to fight for film at every step of the way because it’s important that film doesn’t go away and if no one uses it, then it will go away. In Dune: Part Two, we found that the look that we were after, we could only achieve by using film as an analog intermediate instead of a digital intermediate. And we captured on digital and then went through an analog intermediate.

MATHIESON Film is being steadily being written off by many. It is per frame more expensive than shooting digital, however, there is something I call the hidden dollar. With digital, a camera can run for 45mins continuously on a set per take, you can easily shoot 4 hours of footage a day. At the end of the day, those extra hours all have to be transferred, logged, that directly becomes many hours of burning the midnight oil, extra work for the DIT and digital lab department and editorial. Worse, still no one gets together and watches the dailies anymore, a very important collaboration ritual we would all do to find out what we could do better or to see something that had been very difficult work well. That ritual made us better filmmakers. We don’t we do it? We simply don’t have the time. Why are we wasting so much of our day shooting material that will never make the first assembly? The studios and producers should listen to the people they ask to make films what they want to do, how they see it.

FRAY The more choices we have access to the more expansive our vision! There is something in the image that happens when you shoot on celluloid. Not only in the colors and the way light is captured, but to me it even manifests in the very process of making the movie. When you shoot on film these days, you have to trust yourself and your team in a different way. I think that creates a certain added intimacy with your team and a real singularity of purpose. … I don’t think it’s the right tool for every project, but believe it is the right tool for the right projects.

GUILHAUME It has a real impact on the image; it brings us a simple poetry, it brings magic on the set. The take is sacred; at each take the actors, the team feels absolutely present to the moment.

BROOKS Shooting on film is to light and to understand light. Not having a monitor and learning to trust the film negative, but also trust your instincts, is really important. But for me now, I love shooting digitally. I think the workflow that Jon and I have together, we couldn’t do on film. I love where technology is going … I’m not one of the people that go, “I absolutely have to shoot film.”

LACHMAN Some stories work well with digital, and other stories might work better with film. For me, there’s more depth with film through the RGB layers, and the random grain movement gives anthropomorphic quality like something living, not pixel fixated on one film plain as digital. Colors also renders differently. Film is more like oil paint, and digital is more like watercolor, it doesn’t mix the same way to produce the nuances of colors in the image.

All of your films are visually daring in different ways. We’ve got long tracking and Busby Berkeley-like shots in Emilia Pérez, thousands of extras in a single shot in Wicked, the switching of POVs — which has not been done a lot before — in Nickel Boys, and Greig, you shot in infrared. For all of you, which scene or sequence in your 2024 film was the most complex or challenging for you?

LACHMAN It was very important for Pablo to shoot in La Scala. They’d never let a film crew in, other than a documentary crew. It was finally negotiated, four hours for $250,000, so I had to figure out, “How am I going to go in and shoot this massive scene of this opera with an audience?” They wouldn’t let me in with the pre-lights. I literally went in with 12 PAR cans to bounce off the ceiling. And then I brought in a big projector. And the way I was able to do it was work with their lighting crew because they knew the lights on that stage. And in 45 minutes, we were up and running. The most hair-raising or complicated technical part for me was how to light La Scala in the shortest time I could.

GUILHAUME The most challenging for me, because I had not worked on films of that scale before, was the ending of Emilia Pérez. There is a long night scene where you have mixed interiors in a studio, exteriors that we shot in a quarry near Paris, and full 3D VFX shots that were mixed in, where you can see the cars riding in the desert, and the exteriors are full 3D. It was a lot to figure out, what would be the right balance between all of these elements. What has been said here about the crews is something that’s more and more true. For example, the gaffer, Thomas Garreau, really found a solution for this quarry shot. First I thought about balloons, but he told me that it would be too fragile [with the weather], so we took this 200-foot crane and you have this soft box that naturally lights the set, like the moon. He brought automatic projectors all the way around and was able to shape the space around this final scene where the movie almost ends.

FRASER I think the bigger things get, the harder it is to wrangle. It’s like wrangling cats, isn’t it? Alice’s descriptions of what she went through, it blows my mind. It actually makes me have an anxiety attack. And then ultimately all it ends up being is an emotional shot of a character. You need to record emotion through that lens, and everything else be damned. But if you’re not getting the emotion, then it doesn’t make a difference. You may as well not be there.

John, was shooting with eight cameras at the same time the biggest challenge?

MATHIESON Not so much the cameras. I mean, you’re not going to like all of the frames when you have eight cameras. Ridley will choose the strongest ones, but obviously he wants to try and capture everything at once. A lot of cameras will be sitting there twiddling their thumbs and they’d just be on for five, six seconds. I did spend time in cutting rooms.

I suppose the nights are difficult because you don’t have all night, you have until about 8 o’clock, and we shot the summers during the wrong time of year. The previous film, we shot in the beginning of the year and had a longer light. But also the night, when it comes, it will come late in the evening, and by then he just wants to be gone.

FRAY For us, it really came down to, in thinking about point of view, just how deeply literate everyone is with that perspective. We spend our entire lives inside our own bodies. We wanted POV, but we wanted fundamentally poetic images. So toward that, there was a situation where every single scene we designed as a oner. We wanted to spare the actors more artifice than they were already interacting with, looking into the camera and having these apparatuses for every single shot. And for the lighting with almost all reflective surfaces, I would just surround buildings with mirrors and redirect light into spaces.

It’s an odd thing: If I was trying to think of what point-of-view might look like, I might grab something like a Steadicam, because we as humans stabilize our own vision and our mind. But in reality, it looked more ghostly. So there was a way in which handheld actually feels more present. In another room, I could do handheld and look down on my body and the camera would look down on the actor’s body. So there was a lot of engineering, and each scene needed a very specific camera. They were meticulously designed between RaMell and I to match this feeling of sight and connecting different pieces together. There are so many shots of the movie that I think seem and look simply gestured, but almost every single shot had some amount of intense orchestration.

Alice, what about you? Was it “Defying Gravity”?

BROOKS It was “Defying Gravity.” Jon and I, during our lengthy prep, we talked about the theme of the light is not the light and the darkness is not the darkness. Good is not good and evil is not evil in our movie. I had this idea that the sun would always rise for Glinda and always set for Elphaba. We meet Glinda in her bubble and it’s bright, beautiful and wondrous and Oz is this beautiful, bright space. She meets Fiyero in the morning and Elphaba meets Fiyero at night, and there’s a long sunset sequence that we did through “I’m Not That Girl.” Then in “Popular,” the sun rises for Glinda. The last 40 minutes of the movie, that takes us through “Defying Gravity,” is all one long sunset. I had this image of what the sunset was going to be like, and I had to get everyone on board. Emerald City is our biggest set and it costs a lot more money to shoot at night. We go through the wizard’s palace and end up on top of the highest tower in Emerald City, and Elphaba finds her power as she leaps off a building and into the sunset, as darkness descends.

Paul, much of the first part of the movie is in the dark and daylight only really appears when Emilia wakes up in the hospital, which I thought was very interesting. I’d love for you to talk about that stylistic choice.

GUILHAUME My work was not really to decide that, it was much more to decide what kind of night would be the first act and what kind of night would be the last act and for the first night, it was pretty easy in the way we approached it. I thought, even if we’re in a studio, it should feel natural. The first big musical scene is a market building up Zoe Saldana, who is dancing and singing in Mexico, but that was shot in a studio, and we actually brought a lot of references and even light bulbs that we bought in Mexico, equipped all the lighting stands with wheels and it was equipped with batteries and the choice was to do only practicals for this sequence and obviously with a lot of lighting in them, and the last night was not as contrasty, you don’t have these highlights to fill that the black is black and the colors pop out thanks to these bright lights that you have in the frame.

LACHMAN I think everyone’s talking about a psychological authenticity, whatever style the film that you’re shooting in. You want people to believe what the image represents. And the other thing that I wanted to say is what’s so important is we as the operator, even if you’re not operating, is that we’re another actor. For me, we give a performance in the action with the actors, through light, through movement of the camera, through our movement with the camera, that enhances what the emotions are for the story. And that’s something that I don’t think gets discussed about how the movement is. You know, if acting is acting and reacting, what they say acting is about, that’s really another aspect of what we do as cinematographers is we’re able to interplay with the images, but also with the performance.

Technology is always advancing. Some of you are using new technology on your 2024 films – Alice, I know a new lens was created for Wicked with Panavision. How do you all stay on top of the latest innovations?

FRAY When I’m not on set, you can oftentimes find me at camera houses playing with different lenses and cataloguing what emotional impression they give me so when I’m next thinking of a project I have a wider selection of ideas to pull from. I’m always on the search for images I have never seen before and the tools that can make them a reality.

GUILHAUME Short films, music videos and commercials are a special place for experimenting new technologies.

LACHMAN Technology will never replace the story we need to tell, so that’s what’s important for me.

BROOKS You talk to vendors. NANLUX gave us prototype lights on Wicked that weren’t ready either, that are now their lights. It’s about keeping vendor relationships and knowing what’s about to come out. I’ve got, I don’t know, seven different vendors who have emailed me saying, “will you test these things?” Being in this position is great with a big movie about to come out, and people eager and excited to collaborate with you. … Panavision is my old relationship. … [Back in the day] I couldn’t get a job. I had just had a baby. I had an agent tell me I was way too old to ever be successful as a cinematographer. After flying to L.A. (these people said, we would love to meet with you), I sat down, and they said the reason we brought you in is because we wanted to tell you you’re way too old. And I was 35! I was at a low, low point, and Kim Snyder, who is now the president of Panavision, just kept saying to me, “it’s going to happen. Just stay focused.” She’d take me to lunch, and she’d just be so encouraging. And so that relationship has always been very strong with Panavision. So then, as soon as I knew I was doing Wicked, I called Panavision six months before. I looked at some cameras at the time, but Dan Sasaki [Vice President of Optical Engineering at Panavision] had this idea for a new lens. I couldn’t tell him what movie I was working on, and I showed him my look book, and we started talking about color and image and feeling and emotion. And then he’s like, “I’ve got this idea. I’ll make one, and then we can see how you want to adjust it.” So he made one, and I think it was a 35 millimeter lens, which is what I tested first. I had said we were going to shoot on Alexa Mini and then we tested all the cameras again, because there were also new cameras. When we projected the test at Company 3, I only had one shot from the Alexa 65 and Jon and I looked at each other and we said, “we’re going to shoot on the Alexa 65,” but the lens he was creating didn’t cover that sensor. So I call Panavision, and I said, “can you make this lens these? Can you make this set of lenses for the Alexa 65?” And he said, “No, not on your timeline.” I started testing other lenses, but those lenses were exactly what was in my head, that I had dreamed of. And then we pushed six months, and I called him the day we pushed and I said, “we’re pushing six months. Can you make these lenses now for the Alexa 65?” And he’s like, “let’s try.” And they’re what’s now called Ultra Panatar II, but we called them the Unlimiteds on our movie because they didn’t have a name, and we called them after a Wicked name. But the ones that they made for us are not like the ones that they actually mass produce, and so no one’s touched them. They’re in a closet in London. We have three sets. No one has used them since. No one’s going to use them till we finish movie two.

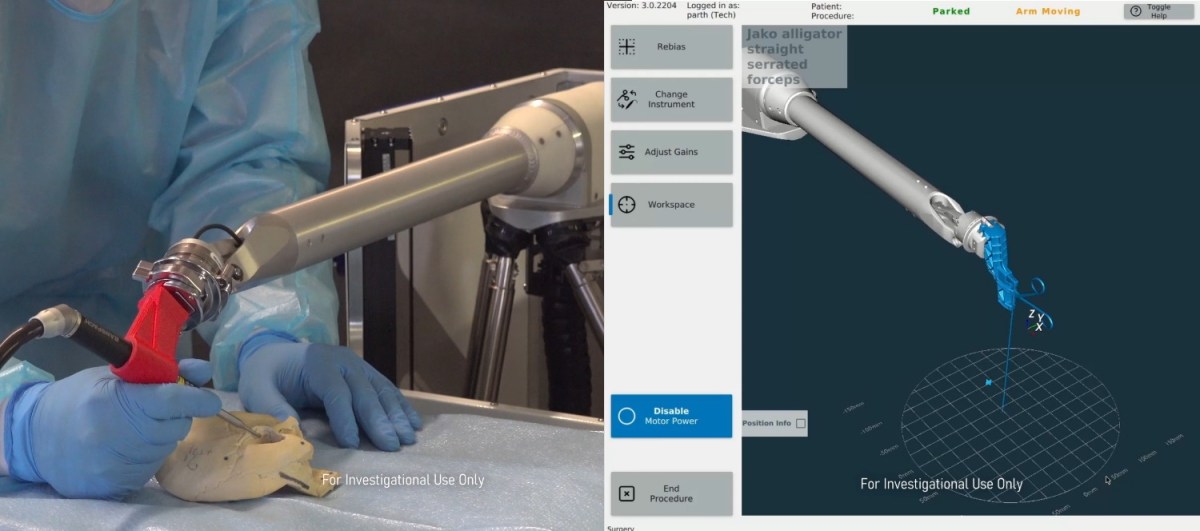

FRASER It does feel like every month something new comes out that changes the game somewhat, and it is hard when you are doing longer projects and you’ve locked into a camera and lens system and a lighting system. Often it feels like when you come out the other end of that, the world’s changed a little bit from when you went in. There are new lights, new brands, new concepts, new ideas. So it is really important to stay on top of it. I do my best to try and test as much as I can, even as we’re filming, particularly gaming 3D gaming engine technology, which I’ve been using now for a number of years from the early days of The Mandalorian and right through to right now where I’m using 3D gaming technology, Unreal Engine, to game out and technically solve problems. We can now do in 20th of the time in Unreal.

The cinematography world is still predominantly white male, as has been reflected in Oscar nominations — only three women have ever been nominated, only three Black people have ever been nominated, and there has not yet been a woman or Black person who has won. Do you see signs that things are getting more inclusive?

FRAY Like all ecosystems, it is when the system is challenged that it is able to continue to evolve and thrive — new growth comes from the infusion of new ideas. I think as a filmmaker and as a film lover that is what I have always wanted from film — to be inspired by others seeing the world in ways I haven’t seen it and to challenge me to integrate different ways of moving through it myself. Film is a space we are able to collectively dream together, the more dreams and dreamers invited to the table the more impactful and powerful our collective art will become.

GUILHAUME I can only talk about what I know which is the situation in France. Here, the cinema schools play a very important role. Inequalities start there, with a strong tendency to reproduce the same population of students from year to year. Some schools work very hard on equality in the admission process and you can see there is a little more diversity among young DPs but big budget films still are almost exclusively shot by white males. It’s like as soon as there is a lot of money involved directors and producers suddenly are much less inclined to diversity and equality.

LACHMAN I can’t personally speak to the why – but what I can do is celebrate the great talent seen in the many female and black cinematographers whose work I admire. To name a few – Maryse Alberti, Alice, Ernest Dickerson, Chayse Irvin, Kira Kelly, Shabier Kirshner, Ellen Kuras, Kirsten Johnson, Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, Rachel Morrison, Mandy Walker, Ari Wegner and Bradford Young – have all shot projects that have moved me and advanced the work done in our field.

BROOKS As of last year, The New York Times published a story that said the lowest branch of female members in the academy was cinematography. When I first went to the ASC, when I was a film student, there were five female members of the ASC. I’m the 20th female member. Now, there’s 25 women out of 415. It’s ridiculously low, considering how many wonderful, talented women there are. … I think there needs to be a clear decision that we’re going to make sure women are being hired on these huge movies. I mean, Wicked is one of the only movies I didn’t interview on. Marc Platt had not seen In The Heights or Tick, Tick… Boom! … We had a rapport, and then he trusts Joh as well. But I think there needs to be more storytellers and filmmakers that are hiring people of diversity. Jon hires people of diversity, and I think there needs to be a conscious effort, because if there’s not a conscious effort towards choosing people from all backgrounds, then there’s just no way it’s going to keep growing. We’re going to stay stagnant.

This story first appeared in a December stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.