Electric Literature Urgently Needs Your Help

For the 15,000 people who visit our site every day, reading Electric Literature costs nothing. And yet Electric Lit is not free. We need to raise $25,000 by December 31, 2024 to keep Electric Literature going into next year. If the continued existence of Electric Literature means something to you, please make a contribution today.

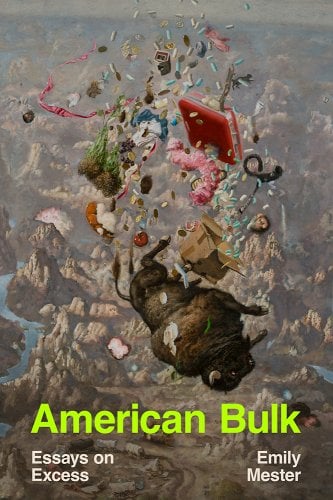

“Shrink,” an excerpt from American Bulk by Emily Mester

Beauty is a growth industry, so said my CEO. She was new to the company, like me, having only arrived during the last fiscal quarter. Before that, she sold cell phones, and before that, McDonald’s, and years ago, Cap’n Crunch and Rice-A-Roni. Now she sold makeup, or I sold it for her, or it sold itself.

Though my store carried several high-end brands, it lacked the luxury pedigree of Sephora, its biggest competitor. You could see it in the bags—theirs, a glossy black that stood up on its own, ours, a pale orange sack. Sephora was the wife of Moses, she who declared her husband the bridegroom of blood after circumcising her son with a flint knife, her name derived from Hebrew, little bird. Ulta is ultra without an r.

My store split its inventory into five basic categories: makeup, skincare, body, hair, and nails. From there, all products were reduced to one of two classes: mass or prestige. The former meant drugstore. The latter meant expensive. Prestige makeup, hair care, and skincare occupied the store’s upper right quadrant, and mass, its left. Shelves of nail polish marked the boundary between prestige face and prestige hair. Hair tools, both mass and prestige, intermingled in the lower left. The salon abutted them. Fragrances rose along the back prestige wall. The registers were neither a supermarket-style row of parallel bays, nor a station along the wall. Instead, they sat around a ring-shaped counter in the middle of the store, arranged so as to be nearly panoptical. We stood anchoring the center.

I started at Ulta in October, having graduated from college the previous May. I’d spent the summer in Chicago getting rejected for unpaid positions at music agencies and copywriting jobs at Groupon, only to crawl back to my parents in August. While I was in college, they made a permanent move to the South Carolina beach town we had vacationed in for much of my childhood. To me, it was a place without time or adulthood or anything but heat and stillness. My mom picked me up from the airport. We passed the Towne Centre mall in landlocked Mount Pleasant, with its twelve-foot-tall stone horses standing sentinel in front of the P.F. Chang’s. We ascended the sloping bridge that connected Mount Pleasant to the island beach town where my parents lived, at the top of which sat an American flag and, for a tall minute, a sweeping view of the Atlantic Ocean. We pulled onto the island’s main drag, lined with palms and clogged with tourists, the pickups and surfboard-laden jeeps trundling along in a slow parade. We turned onto their street, which was a half mile long, no curbs or sidewalks, just a short strip of asphalt bookended by the ocean on one side and marshland on the other. Since the ’90s, houses there were required to be built on stilts so that hurricanes could, rather than sweep the houses away, simply flow through them unobstructed. An old, thick pug stood still in the middle of the street, staring at our car as we veered around him. That’s just Dudley, my mom said, driving past. My parents’ right-hand neighbors had a dolphin-shaped fountain in their yard. Their left-hand neighbors owned a small bungalow that sat flat on the ground, which meant it had survived Hurricane Hugo. Between me and my parents’ front door was a long flight of stairs and a fifty-pound suitcase. I lifted the suitcase gently over the first stair. I could feel beads of sweat forming already on my neck and rolling down my spine into my ass. The air felt like morning breath. Lugging the suitcase up the second stair, I let my arms slacken a little, then on the third stair a little more, until I was dragging the thing behind me, letting it bang violently on every single step. You know I hate that, my mom sighed. I reached the top, breathing hard as I shoved through the stacks of Amazon boxes that would be replaced by a new batch the next day. By the time I started punching in the door code, I’d lost all sense of forward motion. I was again a bored and restless child.

My sleep schedule quickly reversed itself. I would wake up as my parents ate dinner and go to sleep to the sounds of my dad making his morning SodaStream. I didn’t need money but I did need a job, any job, something to differentiate living with my parents at age twenty-three from living with my parents at age fourteen. I applied to and proceeded to hear nothing back from Applebee’s, Target, Costco, H&M, the Container Store, Panda Express, an ice cream cart at the zoo, and Urban Outfitters, which required that I take a personality assessment, the sole purpose of which seemed to be divining if and under what circumstances I would be stoned at work.

Ulta’s ideal employee was someone who needed Ulta more than Ulta needed her.

Only Ulta called me in for an interview. I sat down with Melanie, who had crimpy blond hair that she clipped half up, a southern accent, and the type of black, stretchy, flared trousers that are marked at $89.99 but always on sale for $59.99 under names like The Aubrey and The Blythe and are, somehow, the uniform of every female retail manager at every mall store across the country. She didn’t ask me many questions, but when she looked at my résumé and saw that I’d majored in English, she asked what my future plans were. I paused. My parents had told me to conceal anything that might suggest I had an exit strategy. Ulta, they reminded me, did not want a liberal arts girl with rich parents for whom retail was merely a way to kill time on the way to Brooklyn, graduate school, or both. I’d learned this in high school when I’d looked for summer jobs only to find that summer jobs didn’t really exist anymore, because the people who fill them don’t really exist. If you have money, your summer job is pre-collegiate grooming rituals, all your unpaid internships and philanthropy. If you don’t have money, your summer job is the job you already have. Ulta wanted someone who was likely to stay put. Ulta’s ideal employee was someone who needed Ulta more than Ulta needed her. But in the moment, with my nose ring in my pocket, I panicked and accidentally told the truth. I kind of want to be a writer. She nodded politely.

Our store was located in the upscale-but-not-luxury Towne Centre outdoor shopping mall in the upscale-but-not-luxury town of Mount Pleasant, which was nearly on the water, but not quite. The town is nestled among old-money Charleston, with its million-dollar prewar mansions, some midsize middle-class towns, and a handful of small fishing villages. Mount Pleasant had itself been a small village, but 1931 brought the highway and 1989 brought the hurricane, which decimated the barrier islands. In Hugo’s wake were insurance payouts and talk of new beginnings and, quickly, a real estate boom that never really ended. By the early 2000s its population doubled and became predominantly upper middle class. The new mall opened. Another highway was built. Now, ten years later, its population had doubled again and was sliding toward rich. Not quite Rich rich—Rich rich being an ineffable, ancient stratum of culture and wealth in which almost nobody in America believes themselves to reside—but statistically rich, the kind of rich that thinks it’s upper middle class because it eats at the same chain restaurants as the masses.

On my first day at Ulta, I descended from my parents’ gleaming SUV and walked among the rest of the gleaming SUVs looping endlessly through the Towne Centre’s sprawling parking lot, their reflections shimmering across the windows of the Ann Taylor Loft, the Qdoba, the Hairy Winston Pet Boutique. The white pavement and the shiny cars seemed to magnify the sunlight. It was unseasonably warm that day, so hot the air looked wavy. The brief interludes of heat between icy car and icy store came as a series of shocks to the body, which may in fact be the entire point of outdoor malls: reminding you of your good fortune to be alive in the age of central air.

Dawn, the assistant manager, ushered me to the back room. I wore black pants and a black blouse I’d had to buy from the Old Navy next door. All of my other shirts either had non-sanctioned colors or had been cropped with scissors. My hair was a strange auburn color, the aftermath of a DIY bleach job I’d done a few months ago after watching Spring Breakers. I’d put my nose ring back in after the interview, and Dawn eyed it. That’s fine, she said, aiming to reassure herself as much as me, you’re allowed one facial piercing.

I sat on a folding metal chair as Dawn hit play on a training video. She handed me a headset. The Ulta CEO welcomed me to the family. A robotic female voice told me how to enter my time.

She stood next to me as my first customer approached. In life, my voice is boyish and jocular, but the one that came out was a breezy trill. Did you find everything today? I cooed. Nobody had taught me this phrase or this voice. It’s her first day, Dawn explained as I tried to remember what to press on the register screen. Thanks for bearing with us, I said. Nobody had taught me to say us.

I relished the novelty. I’d always been a shopper, never a seller, and I delighted each time the curtain was pulled back. I learned about the locked perfume cage in the back. I learned new names for the mundane: theft was shrink, a thief was a Thelma, free products were gratis, a customer was a guest and an item they plucked from the shelf and later abandoned was a go back, checkout was the cash wrap, a shelf was positioned by a planogram, a shelf was positioned by mandate from on high, a shelf was a gondola, a shelf was an endcap, a shelf was an étagère. I learned the satisfaction of a workday that dissolved in an instant. The sweet finality of clocking out. I learned just how pale my skin and just how pink my cheeks were. I learned the acute chemical effect of being called pretty a few times a week.

It is perhaps a mark of my comfortable upbringing that the prospect of working retail excited me. But it is also something else. For Christmas one year, my older brother received a toy cash register. I think the idea was to make math fun for him. He abandoned the register after a few hours, but I didn’t. I rang things up well into the evening—I sold myself a Lego, a pop-up book, a wheel for my doomed hamster, a petrified piece of licorice. The items were beside the point. It wasn’t the things that I loved so much as the transaction, the beep of the buttons, the receipt paper smooth between my thumb and forefinger. The way the machine shivered when the cash drawer clicked shut. A friend of mine once declared smoking the perfect sensory experience: you smell it, touch it, fingers, lungs, hot on the inhale, visible on the exhale. It is perfect because your nerves sharpen, then calm. You witness the fact of your steady breathing. You make a habit of it.

Guests who belonged to our loyalty program earned ULTAmate Rewards Points with every dollar they spent. Compared to Sephora, whose Beauty Insider program exchanged dollars not for discounts but for deluxe samples, Ulta’s rewards system was thought to be better, as it provided the illusion of savings. At the time, spending $250 at Sephora got you three-twentieths of an ounce of Intenso Pour Homme. The same sum at Ulta saved you, on the dollar, three-hundredths of a cent.

You needed one hundred points before you could get a discount. I’m sorry, I learned to say to those with fewer, you haven’t yet reached the threshold for redemption. A guest’s point balance was always displayed to me at checkout, but on my first day I was warned never to divulge this freely, at least not before they swiped. The points are an incentive for guests to spend more, said Melanie. If you give that up before they pay, it’s just a free discount.

Instead, I was to do this: Print the receipt and smooth it flat on the counter. Lean over. Underline the fine print. Here is a link to our guest satisfaction survey. You could win a $500 gift card. Raise my eyebrows as if suddenly impressed. Wow. Circle a number at the bottom. Looks like you have 732 points. That’s almost $30 off. Guest frowns. Wait. Couldn’t I have used that today? Well. Conspiratorial. Just another excuse to come back soon. With my neon highlighter I drew a wonky heart.

The slickness of my little script felt balletic. It was a good kind of alien. Soon, stock phrases became mantras, became prayers, became muscle memory. Hi there, If you could just swipe one more time, I apologize for the wait, Are you a rewards member, I’ll take the next guest, You have a great day! I could do it in my sleep.

It was our job to show the guests what they already wanted.

In a pre-holiday staff meeting, assistant manager Dawn taught us the art of the pitch. We were each given an index card with a product’s name. We were divided into pairs and told to role-play as guest and sales associate. The associate would ask leading questions to divine what was on the guest’s index card, which was meant to represent their singular unrealized desire. It was our job to show the guests what they already wanted. Rachel’s index card said Hempz, an organic body cream. The litany began. Are we shopping for anyone in particular? My niece. Does she like hair? No. Does she like makeup? Her skin is dry. Some lotion then? Yeah. Does she like sweet scents? No. Musky? No. What does she like? Dawn called for everyone to wrap up. What does she like? Rachel frowned, flustered, before offering: Weed?

Dawn addressed the room. Some people get shy about it. They tell me, “It feels like I’m selling them something.” And I say, well, she snorted, you are.

I am not shy. For as long as I’ve had a voice, I have loved the sound of it. At five I talked to the dog. At six to a tape recorder. At seven to the mirror, pretending to be in a Neutrogena commercial. I filled my cupped hands with water, threw the water in my face, over and over murmuring cream cleanser, cream cleanser, cream cleanser. I held up a single Mike and Ike in the back corner of a pizza restaurant and pretended to sell Tylenol to the wall. Later, I began to mimic the beauty YouTubers I watched. They all knew to speak in the same strange cadence. The was pronounced thee, the article a became ay. They spoke the same way I did when I interviewed myself on my Little Tikes tape recorder. It was a clicky, rhythmic pleasure, like a girl who has just gotten fresh acrylics and uses them to punctuate her speech. There is no way to represent it without musical notation.

So I went online andpicktup thee Tarte Amazonian Clayyyy . . . Blush? In thee shade Seduce? It izzay pinky. Mauvey. Nude : )

At my store we sold products with names like Bye Bye Pores and Better Than Sex, which is a twenty-three-dollar tube of water and wax. We sold face powders in Warmth and Poured Moonstone, and not one but three One Direction perfumes named, respectively, Our Moment, That Moment, and You & I. Whenever confused husbands came in looking for “some Naked palette,” I explained to them that there were actually seven Urban Decay Naked eyeshadow palettes, and I could, when called upon, spend a good thirty minutes discussing the relative merits of each. A shelf of headbands gathered dust in the neglected center aisle. A sodden cotton ball was stuffed between liquid luminizers. A pink-ribboned curling iron announced its benevolence. For a fee, one of our trained professionals could extend your eyelashes. For a limited time, Mandy could rhinestone your brows. You could buy lipstick in shades Shame and Dominatrix and a few feet away, genuine human growth hormone at $99 a box. A droop-eyed woman with lipstick bleed told me at checkout that it made her hair fall out. I nodded and gave her store credit.

Ulta sold a liquid lipstick called Beso, a true neutral red, and I became the reason it was out of stock. When I wore it, I sold, on average, three tubes of the stuff, just by smiling at the register. It was an acute, specific power. One woman was on the phone with her bank as I rang her up. As she was about to swipe, she put her hand over the speaker, stage-whispered What lipstick is that, and bought it on the spot. I mostly worked the cash wrap, not the sales floor, but lipstick remained my best shill. Whenever I could, I’d swatch the shades side by side on my hand, knowing full well my body sold the pitch. Sometimes, a hand was too small, and I’d clock out with stripes running clear to my elbow. I loved it when my voice sold. The sweet lull of hearing yourself talk crystallizes into an almost narcotic rush when your reverie draws cash. Whenever I’d convince a guest to spend ten dollars on an ugly little breast cancer trinket, or apply for an ill-advised Ulta credit card, I floated to the ceiling. My audience hadn’t just listened. They’d bought.

I sold things I didn’t own. I sold things I didn’t like. I sold things to people who were already buying them. It felt right, somehow, to compliment the customer’s impulses. To confirm them. It felt like the store’s final act of magic, to transform want into need. This is really a must-have, I’d say as I scanned the barcode. We can’t seem to keep it in stock. For a two-week period, a certain brand of rosemary-scented anti-lice children’s shampoo flew off the shelves. It’s always the clean ones, I’d say to the weary moms, beaming reassuringly as if shaking hands at a leper colony. I sometimes sold people to themselves, an act we also call a compliment when it’s done for free. I rang up a tall, skinny, slightly awkward-looking teenager and asked her, wide-eyed, if she was a model. Ulta employees do not work on commission. I worked on something else.

Thanksgiving was rapidly approaching. Sometimes I worked with Teri, who was a full-time CPA but worked at Ulta most Saturdays. Teri was short, blue-black-haired, in her mid-fifties, and interminably jolly. Teri warned me that all the weirdos came out during the holidays. They’re not our regular customers—they don’t act the same.

At 3 a.m., Thanksgiving turkey still warm in my gut, I began my Black Friday shift. I expected madness, fistfights in the aisles, but it was really just more people. For two weeks, my shifts had been a blur of the shrieking fire alarm, which kept going off without cause, and the song “Chandelier” by Sia. On Black Friday, the alarm went off again, this time for thirty minutes. A woman asked Melanie what was going on. Maybe it’s all these red-hot savings, I interjected. The woman laughed, Melanie did not. They were both my boss.

Then the power went out. Is Bed Bath & Beyond out? Dawn implored. The Bed Bath & Beyond next door was a major player in the Towne Centre mall. If they fell, we all did. My coworker Lindsay and I looked at her blankly. We hadn’t been outside in ten hours. A guest who’d just left the Beyond told us their power had come back. Then ours came back. I heard the opening bars of “I Love It” by Icona Pop, which sounded like the fire alarm. The actual fire alarm continued to blare. A woman came to the cash wrap looking frazzled. I asked her for her phone number, as I did all members of our rewards program. I don’t have one, she said. Our house just burned down. At the end of my eleven-hour shift, Dawn’s voice came over the headset—Why did someone wheel a shopping cart in here? We need to get that out of here.

Never mind, she said with resignation a few minutes later, they’ve got a baby in it.

When Teri said our holiday customers were not like our regular customers, I wasn’t sure what she meant. Many of our regular customers were rich—not yacht rich, or summer-as-a-verb rich, but rich enough that Dawn called guest relations putting on your Mount Pleasant.

Our rich customers adopted a mask of good-natured surprise when I told them their totals, sometimes stage-whispering down to their children, We won’t tell Daddy about this. Our rich customers rarely paid cash, but when they did, they used $100 bills. I’ve never seen so many of these in my life, I said to Dawn. Yeah, well, she replied, welcome to Mount P. A few weeks after I started at Ulta, a video of a woman’s customer-service rant went viral. Angela’s search for an out-of-stock Bath & Body Works candle had culminated in a tense standoff with the store’s manager, Jen. Jen had apologized, but Angela wanted more—a better apology, a free gift, a word with corporate, something to mark the spot where she had sought deference and been denied.

Years later, the world would become obsessed with people like Angela and give them a name: Karen, a breed of high-strung, entitled, affluent white woman who demanded servility from everyone around her. When everyone was talking about Karen, I thought back to Ulta. In telling us to put on our Mount Pleasant, my managers suggested that the degree of chipper, coddling deference we showed to the customers was directly proportional to their wealth. The richer you were, the more you wanted from us, the thinking went. But what I quickly noticed was that I acted the same no matter who the customer was. As long as they were buying something, they were also buying me. To be a service worker is to be in constant deference to Karens, yes. But in retail, a Karen can be anyone. Karen is a mindset born less of class, gender, or skin color than of the relationship between employee and customer, which is not unlike the relationship between product and customer. The rich were no more or less demanding of my hospitality, no more or less insistent that I go check in the back, no more or less indignant when the crumpled $3.50 coupon they’d fished out of their purse did not apply to their purchase because, as I had to explain several times a day, those coupons never applied to prestige products, only mass.

We want to believe that Karen’s sense of entitlement is unique to her privilege, that only a profound alienation from the suffering of other people would allow her to act so inhumane. Clearly, people would comment beneath Angela’s video, this lady has never worked a service job. But it seemed just as likely to me that Angela and Jen shared a socioeconomic class, that Angela had worked a job like this, maybe even that she did work one now. I saw it all the time on Yelp, where reviewers foregrounded their disgust by noting that they worked in the very same industry. It seemed to me that one store’s angry customer could easily become another store’s patient manager, and vice versa, that Jen could become Angela and Angela could become Jen, that they could seesaw forever, on the clock and at the bottom, off the clock and looking down.

Ulta was the first time I’d been paid to do anything, and I’d never felt less valuable.

Liberal arts college had been like a summer program for gifted and talented youth, in that my parents paid large sums of money to have my specialness tested and validated through a series of guided activities. I was asked again and again to prove my worth, the assumption being that I had it in vast quantities. Working retail is the exact opposite. You are presumed unspecial the moment you don a name tag, a smock, a novelty visor. You are the public face of the company, a sentient billboard-cum-cash register, and your studied unspecialness—your ability to cede, to blend, to empty—is, in fact, your greatest strength. I knew this before I ever worked a service job, but it still came as a shock. Once, I accidentally shorted a guest $20 in change on her $100 bill and realized it only after she’d left. I agonized over my mistake for an hour, imagining her squinting at her receipt, then back to her wallet, then back to the receipt, cursing my name. When she returned an hour later, I kept repeating I am so sorry, I am so dumb, I am so sorry, I am so dumb. When she smiled and said Everybody makes mistakes, it was as if I was learning the aphorism for the first time. I had been granted grace. I wanted to kiss her feet.

Ulta was the first time I’d been paid to do anything, and I’d never felt less valuable.

The novelty of being a product had begun to twist. Two weeks before Christmas, an older woman approached me looking for lip gloss in a natural pink—the industry calls this an MLBB: My Lips But Better. I launched into a list of several different formulas, all of which I absolutely loved. I finished my spiel and she asked, smiling, what shade of MLBB I was wearing. My chirp dissolved in my throat, my real voice flowing back low and quiet as I told her Oh, these are just my lips. Well, she rolled her eyes, isn’t that nice for you.

One day, a guest complimented my eyes, so I jumped the gun and secretly redeemed her one thousand points for a fifty-dollar discount. Highlighter in hand, I showed her what I’d done, warm with the generosity of my small corporate rebellion. But she was angry. She had been saving her points. She wanted them back. To restore the balance, she would have to return each item and then purchase it anew. Silently, solemnly, she watched me perform our transaction in reverse.

During my first week, I forgot Melanie’s name, and when I asked her, with an apologetic smile, to remind me, she narrowed her winged eyes. You forget your boss’s name? The second time, I accidentally called her Dawn. From then on, my fate was sealed. I couldn’t tell if she just thought I was dumb or if she could smell it on me, the luxury of not having to care whether my boss liked me, the fact that I belonged to the demographic of my customers and not my coworkers, that I didn’t need to be good at the job, for it was as consequential to my livelihood as a weekend pottery class. But the thing was, I still cared. I didn’t need to be a good worker, but I still wanted to be one, desperately.

Dawn—saltier, funnier, lowlier in managerial status—I got along with better, until one day in the break room. Lindsay and I were chitchatting, and I mentioned how I’d learned that, in the state of California, employees got paid lunch. I wish we got paid lunch, I said wistfully as I poked at my Southwest chicken salad. Suddenly, like a poltergeist, Dawn appeared at my side. Say goodbye to the dollar menu, she sputtered. Lindsay and I looked at her quizzically. You wanna pay more for a hamburger? she intoned. Lindsay and I said nothing still. If people don’t want to work at McDonald’s, she continued, then go to college and become the CEO of McDonald’s.

She probably thought you were trying to unionize, my dad explained over dinner. Dawn probably made a pittance too, but her pittance was still our pittance doubled, and she fought for it more viciously than the smirking CEOs who appeared as talking heads on my dad’s Fox News shows. Those men seemed to shoo labor rights away calmly, almost genially, so assured were they of their winning hand. From then on, Dawn was a Melanie too.

As Christmas loomed closer, I began spending almost all my time on register, not floor, and my charisma with customers was becoming a liability; my guest relations were too slow. I was there to grease the wheels of each transaction, nothing more. I needed to trim the chatter until I was checking guests out in two minutes or less. At the time, we were raising money for breast cancer research. A ten-dollar donation got you a clutch or a bracelet. Melanie said we could root around the gratis box if we sold ten of them in a shift, an incentive that seemed less for charity than for the considerably larger gratis I suspected Melanie would get if her store won. Melanie told us to adjust the language we used—instead of Do you want to donate to breast cancer research we should try Would you care to donate or Can I count on you to donate. I didn’t know what was in the gratis box, but I knew I wanted it.

One day, a guest told me that she already donated a portion of her paycheck to breast cancer research. I’m a survivor, she said. So is my mom, I responded, which was true, so I said it in my real voice. We talked for another minute or two. The moment the guest turned to leave, Dawn marched out from the back room with her jaw clenched. Though there were fifty minutes left in my shift, she told me to go home.

My shifts became more sporadic. Sixteen hours one week, thirty-two the next. The exhaustion I felt when I clocked out surprised me. At an office job, you have to dress a certain way, arrange your face into certain shapes, pitch your voice clearer and higher, clench your butt cheeks tighter when you walk through the hallways to your warm little desk chair. Jobs like Ulta demand the same, except there is nowhere to lean. There is no cubicle, no backstage where you can let your entire body slump, and most important, no comfortable salary on which to hang your exhaustion. There are just things to sell, people to buy them, and you. The customer is king, the CEO is divine, and between them, like an isthmus, stretches your cheerful smile. I bought gel insoles. I began to apply antiperspirant to my neck. I learned that guests actually took our guest satisfaction survey. I drove VERY FAST from my job, one wrote, and your shelves looked like WALMART. We’d gotten low marks on door greeting, but the store was kept purposefully understaffed, so Melanie just added it to the cashiers’ duties. My voice went hoarse from screaming Welcome in! over the din. I began to hate how much I hated the job, how I felt ground down by each small indignity, how I felt lowly for not having a sales floor position, how I’d catch myself scrubbing the toilets with too-small rubber gloves and thinking I don’t deserve this, as if there were people who did. I learned that my heart raced with too many eyes on me. I learned a customer’s request that we check in the back would almost never yield the requested product, that when we checked in the back we were really just staring for five minutes at our phones or a wall because the back did not contain rows of stocked shelves so long they merged into the horizon like industrial chicken cages, but rather a cement rec room with harsh lighting containing the remnants of several take-out lunches, unused promotional displays, and a bulletin board onto which management had tacked a grainy black-and-white surveillance shot of two women exiting the store, ostensibly to warn us about these professional thieves lest they return, but really to remind us that we were the store’s most probable thieves. If anyone could beat us at our many-fingered game, it was them, the thieves who paid us.

It was not Dawn or Melanie who fired me, but the bulletin board. When they posted the new schedule, I noticed that I had only a shift on Thursday of that week, and then not at all the next week. When I asked Melanie about it, she tilted her head, not unkindly. Emily, you’re observant in a way that’s good for a writer. Not for a sales associate. I asked her, hesitantly, if that meant I was fired. Well, it’s January, she responded, and you’re seasonal. The season was over.

When I refer to Ulta now, I get the urge to call it my alma mater, an urge I don’t have with the actual college from which I graduated. Maybe it’s because there is no lofty way to say my old job. I avoided entering that Ulta for years, but when I finally returned, nobody I knew was working there. The store looked completely different too—Ulta had capped off a banner fiscal quarter by revamping dozens of locations. Mass and prestige weren’t separated anymore, and the cash wrap now sat along the wall. Later, I looked Melanie up on Facebook. She was pregnant. She was doing something with real estate. She’d posted a selfie. Her lips were a bright, matte red, a true red, not too blue and not too orange. A friend of hers had commented: What lipstick is that? Melanie had replied: Beso by Stila.

Bailey, a third-tier manager who joined in November and whose role remained unclear, was the only other person working on my last day at Ulta. We closed together. She asked me to clean the bathrooms, which I’d like to call symbolic, but it was only procedure. I had already decided what I was going to steal. I knew where the cameras were, where they weren’t, which items had anti-theft stickers, and most important, I knew that the camera footage, due to understaffing, was rarely, if ever, reviewed. I slipped the items into the go-backs basket, stuffed the go-backs basket into a dark corner, and tucked the items in my bra. In the bathroom, I unwrapped them: a face brush that promised optical blurring, and a bright red lip pencil in a shade called Bang. The safest way to steal was to hide the object in dark, tender places where no decent person would root. I walked out of the bathroom with the brush and the pencil nestled tightly against my crotch. All that was left between me and the outside world were the tall, gray anti-theft pillars. I stepped toward them, wincing, bracing myself for the beep.

For guests, the beep meant nothing. Though the threat of theft defined many of our rituals, the guests were insulated from suspicion. We were forbidden from chasing customers out of the store. We were functionally forbidden from confronting them in-store too, allowed to do so only if we could keep the customer in an unbroken line of sight. If they turn a corner or go behind a shelf, Dawn warned, you can’t say anything. They could’ve put the thing back. If the pillars beeped for a customer, they would look back at the cash wrap either nervous or irritated, and we’d wave them through regardless.

The gray pillars had beeped for me once as an employee. When it happened, I panicked, though I had stolen nothing. I dug into my pockets, patted myself down like the TSA, pulled out every item in my clear plastic tote bag, the same kind required in stadiums to ensure you don’t sneak in outside food or a handgun. My sweater, I’d panted finally to Melanie, who didn’t seem fazed either way, they forgot to take the tag off my sweater.

Six years later, I stood in line at a Las Vegas Target. In my cart were eighty dollars of overpriced groceries and a nail polish I’d decided, at the last minute, not to steal. I noticed a group of teenage boys approaching the checkout with armfuls of Grey Goose and Patrón bottles. When they got up to the registers, they walked right past, their steps purposeful but unhurried. They continued heading toward the door. Everyone—the customers, the cashiers, the security guards—stood still and watched in awe. As the teenagers stepped through the pillars, the alarm sounded. Nobody bolted, nobody hid. They knew the beep meant nothing. The store couldn’t chase them if it wanted to. Crossing the threshold, one of them turned back around to face the crowd, gripping the necks of the bottles and raising them into the air as he bellowed WE DON’T GIVE A FUCK. The alarm kept beeping as the boys walked out into the sunshine. I’d never heard a feebler sound.

If the gray pillars beeped as I left work on that final day, I planned to bolt through them and head for the parking lot, to run until I was a customer again. But they didn’t make a sound. As I began to push the doors open, almost in the clear, Bailey held out her arm to stop me. I froze. Bag check, she said dully. I’d forgotten. I opened my tote and she peered down into it. She nudged aside two tampons, a fork from home, a water bottle from the break room vending machine. She stopped when she found a tube of Lipstick Queen lipstick that I’d bought from Ulta years earlier, before I ever worked there. Then she turned it upside down, searching for the dot. On my first day, Melanie had marked the bottom of the tube with a green dot of paint so that every time she checked my bag, she’d know I hadn’t stolen it. Dots were also given to my glass pot of concealer and my bottle of rosewater face spray. When I bought a tube of hand cream with my employee discount, it got a dot too. If I owned anything that Ulta sold, the dot was the only thing that let it cross between the two worlds, the one where Ulta belonged to me and the one where I belonged to Ulta. I still have the lipstick, and it still has the dot, which was made to show that it was mine, it was mine and not theirs, not theirs but on loan to them, until I clocked out.

Excerpted from American Bulk: Essays on Excess by Emily Mester. Copyright © 2025 by Emily Mester. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

This selection may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

.jpg)