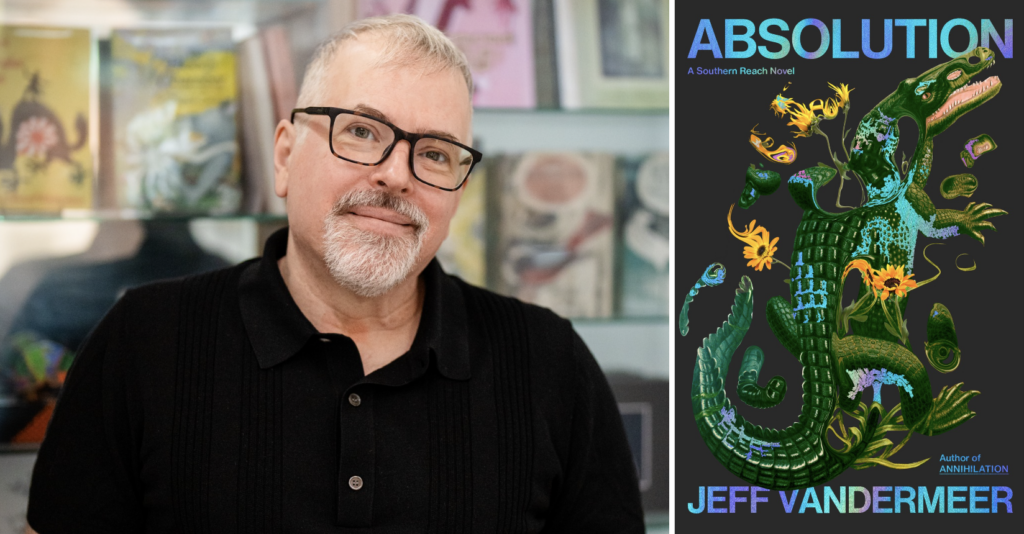

It’s been 10 years since the publication of Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, the first book of his acclaimed Southern Reach trilogy. Since then, the mysterious coastal zone known as Area X, where much of the series takes place, has become for many readers a shorthand for a kind of crossover into an unknowable (mind-blowing) realm. Area X resists comprehension and changes everyone who enters it; human attempts at mastery over the environment falter as the seemingly benign natural world becomes alien—and we encounter the wonder and terror of our own dissolution.

For me, the crossover into Area X also signifies a dismantling and rearranging of language and conventional narrative. With each foray into the territory, VanderMeer reinvents the way a story can be told. Genre tropes associated with sci-fi, mystery, fantasy, and weirdness are expertly deployed and deconstructed. The series, and VanderMeer’s work at large, shows how existing systems for describing this world fall short.

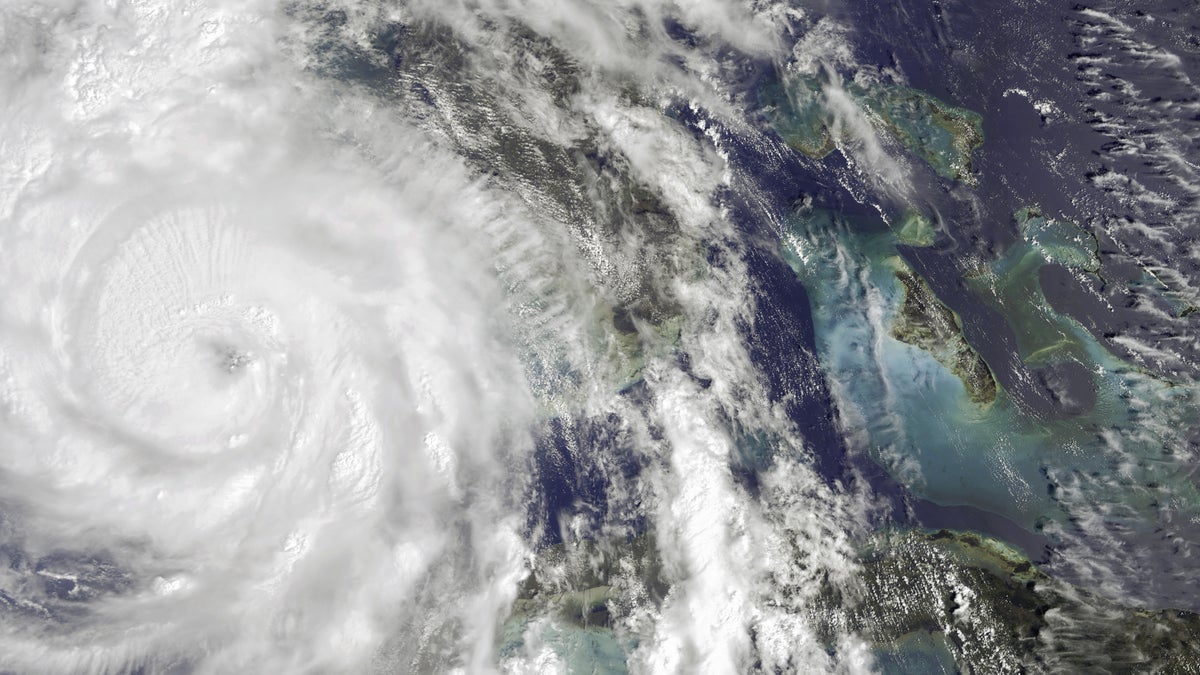

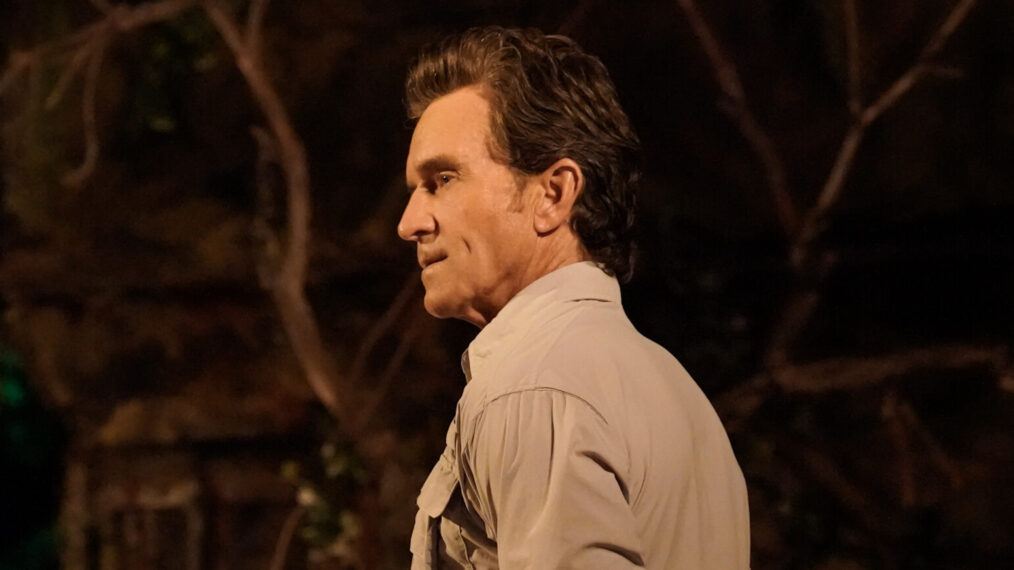

The mega-volume Absolution takes us into the prehistory and early years of Area X, moving masterfully between past and future in a prescient exploration of power dynamics and system breakdown in the face of environmental and political collapse. I talked with VanderMeer just after Hurricane Milton had swept his home state of Florida to talk about the derangement of our time and what it’s like to write about—or during—ecstatic visions of another world.

*

Elvia Wilk: I love seeing the anticipation of this book from fans online.

Jeff VanderMeer: I’ve been posting photos of the book. I started doing this thing where I deconstructed a copy and let it just sit out and decay, then set it on fire, then put it in a jar. And at some point it’s like, am I doing PR? Is this off the rails?

EW: I saw somebody growing mushrooms out of a copy of Kafka’s Metamorphosis online today. I think you started something.

EW: I saw somebody growing mushrooms out of a copy of Kafka’s Metamorphosis online today. I think you started something.

JVM: That’s pretty on point.

EW: I wanted to ask how you’re holding up in the hurricane aftermath. How are things in Tallahassee?

JVM: I had this experience where I was asked to write about the hurricane for the New York Times—while I was fleeing the hurricane. But I also had chosen those days to do a Grub Street diet piece for New York Magazine.

EW: You were escaping and also trying to find cool places to eat?

JVM: Yeah. What made that even more surreal is that downtown Greenville, South Carolina, where I decamped to, was the only place in that city that had electricity continuously, because it’s so economically important—which is a knotty issue. So I had this bizarre experience of being in this oasis of electricity. All the fast food places were closed, and the only places that still had food were the fancier restaurants downtown. Also, the lab had mixed up my blood test with somebody else’s, and I went around for that entire week thinking I had cancer, and couldn’t talk to my primary doctor because he had fled the hurricane. In the middle of that, I learned that a tree had gently fallen on our house. And our cat Neo passed away while I was in Greenville.

EW: Oh my god.

JVM: So strange. So meta, existing on these different levels all at once.

EW: I’m so sorry. You must be exhausted. What a microcosm of everything that’s wrong. It’s hard not to turn this into a climate-change-in-a-nutshell story.

JVM: Exactly. The psychology behind “resiliency” can actually be bad when we have to do these structured retreats from storms. If you’re writing books that are grappling with climate crisis, you have to think about dysfunctional systems that are not up to the task.

EW: Right, because resiliency implies something to return to, like we’ll just go back and rebuild and reverse the catastrophe. But transformation is irreversible. That’s one thing that the Southern Reach series is about: how ecological change can’t be undone, and how it changes us as we experience it. Now that I’ve read the new book, I’m wondering whether you, the author, have also crossed some kind of border in your own writing. You are so in the weirdness of Area X in this book.

JVM: I think the readers gave me permission not to come back across the border. If they hadn’t, maybe I would have had some constraints on my imagination. I just felt total freedom to write the book exactly the way I wanted to. Absolution has much weirder stuff going on than the first three—the character points of view, the style. I thought of there being almost a kind of medieval point of view towards the end. I had to think of archaic language and its relationship to the current moment: what’s outdated, what’s timeless.

EW: I’m glad you say that about archaic language. The last section reminded me a little bit of the novel Riddley Walker by Russel Hoban, which takes place in a post-nuclear future that resembles the Middle Ages. It’s written in a made-up language that suits their demolished world. You’re also taking language apart and reassembling it.

EW: I’m glad you say that about archaic language. The last section reminded me a little bit of the novel Riddley Walker by Russel Hoban, which takes place in a post-nuclear future that resembles the Middle Ages. It’s written in a made-up language that suits their demolished world. You’re also taking language apart and reassembling it.

JVM: The first part of the book is about this expedition of biologists 20 years before Area X occurs. I thought increasingly about their isolation and how they’re being thrown back in time. The landscape around them is practically prehistoric. That kind of timeless permanence is something I notice on the Forgotten Coast [of Florida], ever since I started hiking it in 1992. It has not changed. And yet so much has changed in the world. The farther out you get, the more you feel like you’re going back in time, because the landscapes become more primordial.

EW: Landscape as time travel.

JVM: Absolutely. I thought the biologists’ encounter with Area X would be similar to people from medieval times encountering something inexplicable that they then had to contextualize. That contributed to a style that incorporates archaic words and syntax, or an approximation that is fluid enough to be modern. The moment when [a creature called] the Rogue finally appears to the biologists is literally like an ecstatic vision from medieval times. I have this book from Taschen, The Book of Miracles, which has all these art pieces of comets and meteorites, and it gives context as to what people thought they were back then. That was on my mind, because the last scene I wrote in the last book, Acceptance, is one where [the lighthouse keeper] Saul has this ecstatic vision, or this warning of a comet coming to ground and not knowing what it is. It’s not the last scene in the book, but it’s the last scene I wrote for it.

JVM: Absolutely. I thought the biologists’ encounter with Area X would be similar to people from medieval times encountering something inexplicable that they then had to contextualize. That contributed to a style that incorporates archaic words and syntax, or an approximation that is fluid enough to be modern. The moment when [a creature called] the Rogue finally appears to the biologists is literally like an ecstatic vision from medieval times. I have this book from Taschen, The Book of Miracles, which has all these art pieces of comets and meteorites, and it gives context as to what people thought they were back then. That was on my mind, because the last scene I wrote in the last book, Acceptance, is one where [the lighthouse keeper] Saul has this ecstatic vision, or this warning of a comet coming to ground and not knowing what it is. It’s not the last scene in the book, but it’s the last scene I wrote for it.

EW: What I love about accounts of that type of inexplicable occurrence is they’re often ambivalent: this is both awesome and terrifying. Salvation or doom? The start of an era or the end of an era? How to explain it. I don’t know many writers today who are so effectively confronting the limits of language while also telling a story.

JVM: That’s the conundrum, right? I learned a lot from Angela Carter, who I feel was able to make surrealism in writing more accessible—not in a way that’s more commercial, but by channeling it into a recognizable narrative, without distilling that thing to the point that it becomes something weaker. I went as far as I possibly could in my book Dead Astronauts, which tests the limits of comprehension.

JVM: That’s the conundrum, right? I learned a lot from Angela Carter, who I feel was able to make surrealism in writing more accessible—not in a way that’s more commercial, but by channeling it into a recognizable narrative, without distilling that thing to the point that it becomes something weaker. I went as far as I possibly could in my book Dead Astronauts, which tests the limits of comprehension.

EW: Have you had an experience like that? An ecstatic mystical encounter?

JVM: It’s not the same thing, but when you’re in deep wilderness and you’re cut off from your technology—this is one thing that North Florida and parts of the Pacific Northwest have given me—and you encounter something and you don’t know what it is at first. In the distance, things can manifest as one thing and coalesce into something else. The thing you thought was a bear turns out to be a boar, to give a very prosaic example. Especially at dusk or dawn, you enter these kind of liminal moments with the light, and your mind defaults for a moment to things that are not real. That’s probably the closest in terms of actual experience—the ecstatic brightness and light shining through in primordial places is extremely suggestive of another world. I channel those emotionally jolting moments I’ve had, where your view of the world or of other people changes fundamentally, and it’s a shock. That has happened to me maybe four or five times in my life. It doesn’t make any sense on a textual level, but on an emotional level.

EW: My husband and I were on a small island off the coast of Sicily this summer, and we had an experience a few times where, in the dark, we thought a plant was an animal. We’d see something moving towards us in the darkness and jump, and then realize it was actually an alien-looking plant. We’d say—that’s a VanderMeer plant.

JVM: Right!

EW: Why are so many of your characters biologists? I’ve always read it as a way of investigating how taxonomies can only go so far to describe what we see.

JVM: There are separate reasons for separate contexts. In Absolution, I loved the idea of the biologists knowing a lot about the landscape but less about it culturally—being both outsiders and insiders. Science is not an objective thing because it’s still expressed through scientists. We see all kinds of examples of what this means in terms of bias and how it contributes to misogyny and whatnot.

I was teaching in upstate New York for a semester, and I volunteered for this owl banding thing at night outside of Ithaca. When I got there, it was a little bit like Lord of the Flies meets volunteering. It wasn’t clear that it was scientifically necessary or that it was best practices. The guy in charge seemed to be doing it ritualistically, which was interesting from a writing point of view.

I was teaching in upstate New York for a semester, and I volunteered for this owl banding thing at night outside of Ithaca. When I got there, it was a little bit like Lord of the Flies meets volunteering. It wasn’t clear that it was scientifically necessary or that it was best practices. The guy in charge seemed to be doing it ritualistically, which was interesting from a writing point of view.

I took a photo that shows this quintessential moment of alien derangement. There’s a spotlight on a small table where someone’s holding an owl and they’re about to take a blood sample for parasites, and you can’t see the researcher’s face in the photo, just the hand holding the owl in this reclining position looking up at the researcher—and I’m anthropomorphizing a little bit, but the look on the owl’s face, it felt like a moment of alien abduction. The photo was both disturbing and oddly beautiful in terms of the clarity of the instruments on the table, the way the owl was being held. It could have been a scientific still life done by a 17th- or 18th-century painter.

That was all on my mind with regard to the expedition of biologists. These unintended consequences and ways in which the bias comes in, even in things that we think of as positive and that usually are.

EW: We change the environment as we try to preserve it. And these encounters change us too.

I think that’s partially why the scariest characters in Absolution are the mutant alligators and the carnivorous rabbits. They also have these unstable media objects attached to them; the rabbits are wearing dysfunctional cameras, and the alligators have tracking devices, but the photos aren’t right, and the location data isn’t reliable. The evidence or data is fucking with the biologists’ idea of their own mastery.

JVM: The biologists encounter them and then try to contextualize them and label them, put them within a rational context—and they have to do so more intently than your average layperson because that’s their job. So in a way their job makes them less able to see what they’re actually seeing. I found that to be an interesting conflict because there’s practical reasons you might run screaming from something terrifying. But the context and framework in which you encounter it is such that you don’t think to engage in the usual kinds of questions.

EW: I guess the question you should ask is: am I insane or is the world not the world I thought it was? Which is the question everyone has to ask themselves in Area X.

The book begins 20 years before Area X, then fast forwards to 18 months before, and then fast forwards again to 18 months after. In some ways it’s three books in one. I know you use note cards. Did you have a million times more note cards than usual in your writing space?

JVM: I have boxes and boxes of them for this novel. And this time, someone had sent me all these library catalog cards that have been discontinued. So I used the backs of those, and that was a kind of sympathetic magic—sometimes I would turn it over and read what the library card actually described and it would give me an idea for the novel.

EW: That kind of associative thinking really comes through in the text. All the Southern Reach books have ghosts of the other books in them: bits of reworked dialogue or descriptions that crop up again. One type of ghost text I noticed in Absolution was the hypnosis cues from Annihilation. I felt like maybe I was being hypnotized while reading. The reader’s recall experience is so layered.

JVM: The recall is complicated, too, because I had to push against a secondary desire to please the reader who has read the first three books. To please that reader, I would have had to put in more references to characters that are irrelevant to Absolution. I had to really be disciplined about only putting in what was needed.

EW: For me, the most profound (human) relationship in this book is between Old Jim, an operative from a secret agency called Central, and his daughter. The intergenerational aspect is so carefully rendered.

JVM: I think it’s very rare to find depictions of intergenerational relationships like that in literature that are not clichéd. I spent a lot of effort on that dynamic very specifically, and in a very realistic sense how it would manifest and how Cass, the younger woman, would feel in that context.

EW: But the daughter is not really… the daughter. She’s a doppelgänger.

JVM: I’ve always dealt with doppelgängers in these books. I read a book by Tana French, The Likeness, that put all kinds of questions about identity in the back of my mind. In it, a detective dies, but a detective who looks like her takes her place the next day. It’s a stunning conceit because it shouldn’t work—but it works because the characters she knows all have reasons to support the fiction.

JVM: I’ve always dealt with doppelgängers in these books. I read a book by Tana French, The Likeness, that put all kinds of questions about identity in the back of my mind. In it, a detective dies, but a detective who looks like her takes her place the next day. It’s a stunning conceit because it shouldn’t work—but it works because the characters she knows all have reasons to support the fiction.

EW: The idea of people being interchangeable is terrifying. I hate to think I could be replaced in my life. On the other hand, that would also mean I could disappear and become someone else, which is liberating.

JVM: That idea comes out with Old Jim, where I layered in a little bit of his history with his handler, Jack, to the point where you feel like Old Jim has become different people at different times in his life. It was interesting to think of doubling as a speculative idea—but also as a character reality, something you might find in a realist novel that has no speculative element whatsoever. This book probably has the most uncanny elements of any novel I’ve written, but I think it still adheres to what I think readers respond to in the first three books, which is that the underlying psychological dynamic of the characters creates a resonance that matches the speculative elements.

EW: I agree. The fallibility of memory and instability of identity are not speculative issues and they don’t rely on speculative devices. And in this case there’s a sinister aspect to the identity confusion: Old Jim’s memories are seemingly manipulated by the people he works for. I’m wondering how you think about that conspiracy element of the books—in this book I felt like there was less of a unified conspiracy.

JVM: I can’t get this image out of my head: the image of Elon Musk’s face genuflecting to Trump on the stage. He’s on one knee looking up and he’s in this twisted production of Shakespeare—maybe he’s the Jester in Titus Andronicus. It felt very archaic to me. I feel like we’ve reached the point where we’re not even pretending that corporations and certain governments are trying to be logical rather than just be the reflection of their founder. That played a role in how decentralized stuff becomes in Absolution, and you realize that Central was more chaotic than you thought. I became fascinated by factions in Absolution. Originally there were like five different groups, but it was becoming like a bad Le Carré novel. I stripped that out because that wasn’t the point. There needed to be more emphasis on the individual characters and their interiority.

JVM: I can’t get this image out of my head: the image of Elon Musk’s face genuflecting to Trump on the stage. He’s on one knee looking up and he’s in this twisted production of Shakespeare—maybe he’s the Jester in Titus Andronicus. It felt very archaic to me. I feel like we’ve reached the point where we’re not even pretending that corporations and certain governments are trying to be logical rather than just be the reflection of their founder. That played a role in how decentralized stuff becomes in Absolution, and you realize that Central was more chaotic than you thought. I became fascinated by factions in Absolution. Originally there were like five different groups, but it was becoming like a bad Le Carré novel. I stripped that out because that wasn’t the point. There needed to be more emphasis on the individual characters and their interiority.

EW: There’s the ghost of a spy novel though. Do genres feel totally recombinant to you?

JVM: To some degree, you write by feel, and then as you have a sense of the outlines, you begin to think about the proportions. When I’m recombining a lot of different tropes, I ask how what I’m doing differs from what the reader expects from that trope. If I’m substituting something, it has to be as satisfying — there’s a reason why we have these genres. Sometimes when you recombine things from vastly different genres, you can find a pressure point where it’s deeply disturbing or uncomfortable, but isatisfying.

EW: What’s being absolved in Absolution?

JVM: People who actually need absolution often don’t think they need it. I specifically thought of Old Jim in this way—I like to explore a character who can be sympathetic on one level but compromised on another. He has some agency—but we often don’t have much agency in the face of systems, and yet we don’t forgive ourselves for not being able to operate under them. This goes back to the hurricane stuff—in the U.S. we still believe: roll up your sleeves, do the work, and good things will happen. Well, under deranged systems, under extreme weather, you have to throw a lot of that out the window. There are ways in which the themes of these titles occur to me consciously and then just ways in which they feel right.

EW: Last question. This book is being talked about as a surprise addition to the trilogy. Was it a surprise to you?

JVM: Yes and no. I wrote the first nub of [the first section], “Dead Town,” in 2017, I think. And I loved the tone of it. But I was like, who is telling this story? And I didn’t know. There was also another story that I tried to put on paper too soon. I was canoeing and I saw this island of dirt and grass coming towards me. It turned out that it was some meteorological experiment—there was something below the surface that was tracking something and had a little engine on it. But the bobber above had gotten so entangled in stuff over the years that it had formed a dirt island that was floating on the surface. At first I thought that this was a biology experiment that had gone wrong, and there was some alligator or a manatee in a harness underneath the surface that was pulling it. I tried to put that in a short story called “The Birdwatchers,” which included versions of Old Jim and Jack in a boat on the Forgotten Coast, and it wasn’t really working.

But by the time that I sat down on July 31 of last year, I had had this vision, where I had the entire structure in my head. And then I just wrote continuously for six months. In the past when I’ve been overtaken by ecstatic visions and things, I don’t talk about it as directly because it feels like people want there to have been a rational process by which a novel comes out. But I was just overcome by it. A lot of the moments of writing the novel were like that for me. I literally felt like I was there in that moment, experiencing what the characters were experiencing. And I just wrote for six months. I didn’t leave the house. I was wrung out by it, but it was definitely a very satisfying writing experience.

EW: So maybe some of your ecstatic visions come to you while writing.

JVM: Exactly. I don’t know how to describe it. To feel like you’re there in that moment and that the language has to somehow reflect some tactile experience that you haven’t actually had before is a little bit new for me. That’s what it felt like.

![‘Monarch’ Boss on Killing Off [Spoiler] & Susan Sarandon Making Dottie’s ‘Over the Top’ Move Seem ‘Natural’ ‘Monarch’ Boss on Killing Off [Spoiler] & Susan Sarandon Making Dottie’s ‘Over the Top’ Move Seem ‘Natural’](https://www.tvinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/monarch-107-dottie-albie-1014x570.jpg)